Tina Rivers Ryan on falling in love with Art History, Navigating Audiences, and Motherhood in the Art World

by :

Emily Ebba Reynolds

Photo: Nando Alvarez-Perez

Three years ago, before either of us were living in Buffalo, I met Tina Rivers Ryan at a wedding. Months later, she was in San Francisco and came to an opening at my gallery. She mentioned that she was interviewing for a job at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. She knew that I’d spent a little time here because my boyfriend’s family live here. She got the job (Assistant Curator), and about a year later my boyfriend (now husband) and I moved back to Buffalo as well, where we’re all part of the larger arts community.

Since joining the Albright-Knox, Tina has worked on seven shows, including Introducing Tony Conrad: A Retrospective, We The People: New Art from the Collection, and two shows in the Gallery for New Media. She is also an art historian, a critic whose words you can read in art rags and academic journals, and an active public speaker who travels the country giving lectures to audiences of all kinds on topics ranging from Michelangelo to digital art.

“I have a special love for anything that plugs in, or turns on, or blinks, or makes weird booping noises.”

I sat down with her to talk about how she got into art history and, more specifically, media art; the ways she navigates audiences; and what life is like as a new mother.

Emily Reynolds: Let’s start with the beginning: When and how did you get interested in art?

Tina Rivers Ryan: I grew up in a family that appreciated the arts but didn't necessarily know a lot about them. My mother thought it was important to take me to art museums, but she herself had no formal education in art. She wasn't an artist and never took an art history class, but she thought that appreciating the arts was part of being a generally educated and well-rounded citizen. So I was exposed to a lot of art as a kid but had no real training to understand what I was looking at.

When I went to college, I thought I was going to be a history major and focus on the European Middle Ages. One of my distribution requirements was in the arts, so I signed up the spring of my freshman year to take a class on Surrealism. I picked Surrealism because, like most teenagers, I thought Salvador Dalí was kinda cool. Also, I grew up in Miami, and my mom had driven me over to The Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. But in that Surrealism class, I fell completely in love with art history—to the point that the next semester I changed my major.

ER: Wow, fast.

TR: I really, really loved it. It was another way of doing history, and I realized that what I really loved about history anyway were the visual artifacts. I realized that you could look at objects and learn and write history through them, and that, to me, seemed like a much more exciting way to do history than staring at a bunch of Latin documents.

After switching, I did feel like I was at a disadvantage, because I was in classes with other students who had taken art history in high school, or had grown up in cities like Los Angeles with world-class museums, or had parents who were art collectors, or knew artists personally. In my classes, people would refer to certain painters or movements, and it would be assumed that everyone knew who and what they were; I just had no idea.

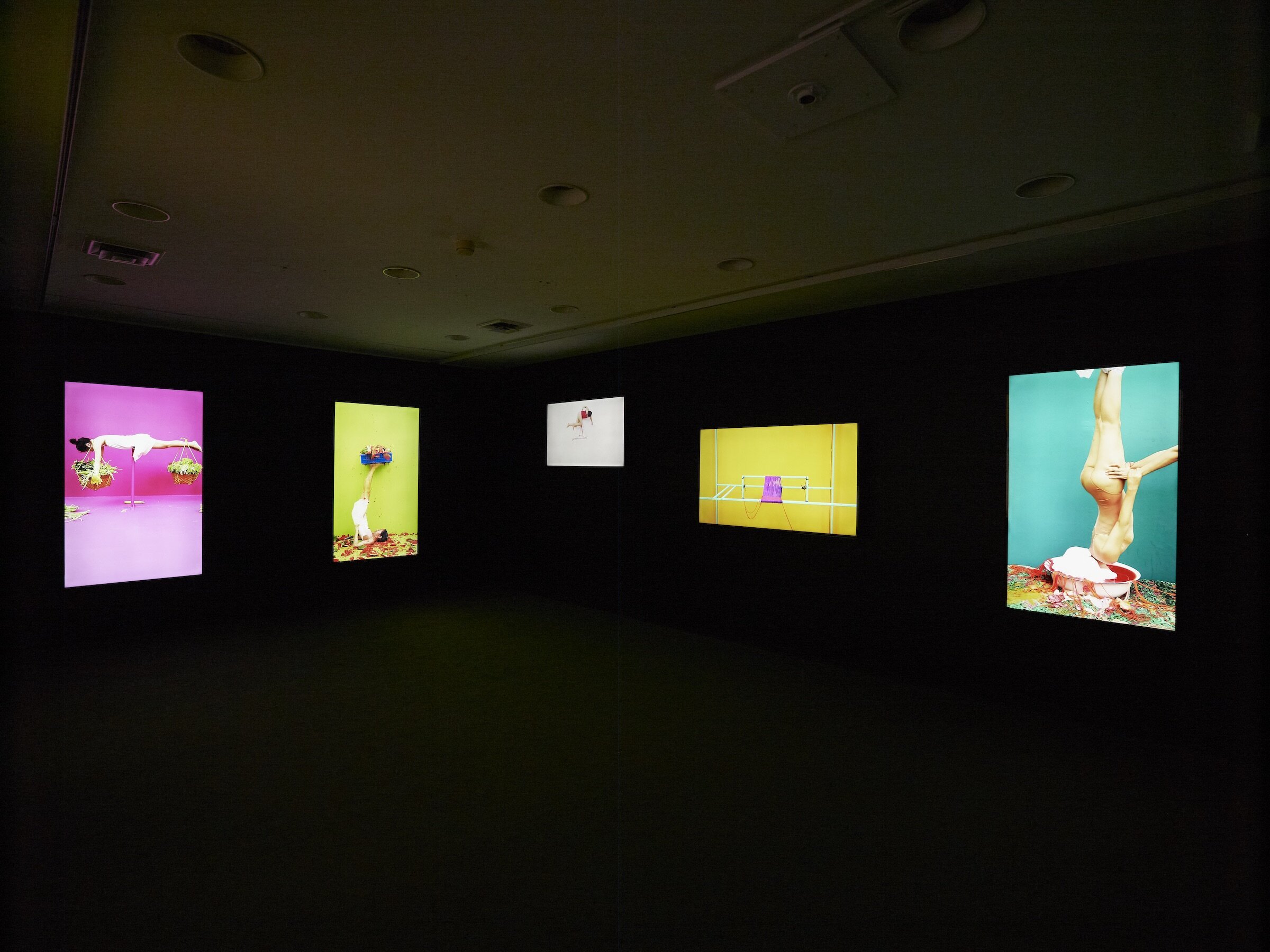

Installation view of Kawita Vatanajyankur: Foul Play, curated by Tina Rivers Ryan. Courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

ER: So did you switch to medieval art?

TR: I never thought about being a medieval art historian, which I think is funny. I immediately switched to the 20th century.

ER: What drew you to media art initially?

TR: I should start by saying that I am not technically a curator of media art at the Albright-Knox—we’re a small enough team that we all have to do a bit of everything—but it is common knowledge that I have a special love for anything that plugs in, or turns on, or blinks, or makes weird booping noises. It probably started with a love of experimental film that I think relates to coming of age in the 1990s and early 2000s, which was the golden age of experimental music videos, and also to growing up around technology: my mom studied computer science and has always worked with computers, so I was around computers from an early age. I got my first dialup modem and AOL account right when I was figuring out who I was, or wanted to be. I think my mental picture was Angelina Jolie in Hackers, which never exactly panned out.

ER: As well as a curator, you’re also a writer/critic. Can you talk a little about how you navigate the two roles? In what ways are they connected?

TR: I was a critic before I was a curator. As a graduate student, I realized that I was working on these seminar papers—and, ultimately, a dissertation—that each took months or years to complete but very often would never see the light of day. I thought that writing criticism would be a fun way for me to work on a much shorter time frame, and also a way to get some of what I was working on out into the world.

When I started publishing criticism in 2013, it required me to be much more involved and invested in contemporary art—as opposed to 19th or 20th century art, which was my area of academic expertise—and also more succinct. Now, as a curator, I can see that writing criticism also pushed me to think even more about my audience and how I communicate my ideas. Writing for Artforum is, in many ways, very different from writing for a general public as a curator, but it’s closer than academic writing.

Installation view of Aria Dean, curated by Tina Rivers Ryan. Courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

ER: One thing that I’m struck by in your writing and curating is how you navigate audiences—you can give one of your lectures for a group of art novices and then write a piece of scholarly work on the same topic and I think the two audiences might almost come out with the same acquired knowledge. How do you do that?

TR: Well, first of all, that's very generous of you to say—I really appreciate it! That’s exactly what I'm trying to do. I want to make things accessible without dumbing them down. I think there's a real misunderstanding (among academics, at least) about the work that museum education departments and curators do—that, somehow, we take objects or ideas that are very complex and then sort of dumb them down for the public. I don't think that's what we do. It's not what we should be doing. I think that we have a responsibility to enrich the public’s experience of art by introducing them to new ideas and new skills, but to do that, you’ve got to meet them where they are. Conversely, there’s a perception among museum folks that critics and academics are engaged in a discourse that isn’t relevant to the general public, and that’s not necessarily true, either. Basically, I think that you can make any material relevant to any audience—it’s just a matter of connecting with them so that you can understand why it might be relevant to them and then explaining why it’s relevant in terms that will resonate with them.

That means the first step is just to know your audience and to listen to them. My very first question whenever anybody asks me to give a lecture or to write something is, "Who is this for?" And when we are planning an exhibition, one of our first steps is to meet with the Education Department and ask ourselves internally, "Who is the intended audience for this exhibition?" It's not necessarily the case that every exhibition is intended for everyone, for all audiences, and the same is true for every text.

Depending on your audience, you can do things like modulate your vocabulary, just making sure that you are using words that either everyone will understand or that you can explain easily. I try not to presume any prior knowledge, because if you’re introducing names and concepts in a way that implies that everyone should already know them and someone doesn’t know them, they automatically feel excluded. It’s really important to make sure that you're bringing people along with you.

“In a sense, I’m trying to sell people on art. I care if they learn—that’s very important to me. But it’s also important that they fall in love with the experience, and that they come back for more.”

ER: It strikes me that you said that about your first art history class: people were talking about things you didn't know but were presumed to know.

TR: Funny—as I just said that, I also had that epiphany! I was an art world outsider before I was an insider, so I can identify with that experience. Maybe that memory is still very fresh.

Aside from knowing your audience, what I think is more effective than almost any other strategy is conveying your enthusiasm and showing people why you love art. In a sense, I’m trying to sell people on art. I care if they learn—that’s very important to me. But it's also important that they fall in love with the experience, and that they come back for more.

ER: Should we talk about your non-art life? You are a mom! Has being a mom changed your relationship to art? To work?

TR: That’s a really interesting question right now: As a society, we’re paying more attention to the challenges faced by all caregivers, and particularly mothers, in the workplace. At the same time, motherhood has become a really big topic in art: a few prominent artists have made works about birth recently, for example, and the curators Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick are developing a project called Designing Motherhood. I think all of this interest is probably related to the Me Too movement, and the fight for equal pay, and the rise of intersectional feminism, and new understandings of gender: in this moment, feminism is being reinvented, and that includes motherhood, too.

Personally, when I went back to work after giving birth, I texted one of my friends who is also a mom and was like, “I feel as if I'm just two different people inhabiting the same body.” I think that over time I will learn how to better integrate work and motherhood. Or maybe not. I'm not sure how it's going to work, to be honest, and I think that’s partly because we’re continually rewriting the rules.

As far as my response to art, it’s cliché, but I'm kind of more drawn than I used to be to things that are light-hearted and joyful. But they still have to be rigorous and conceptual, of course!

ER: What’s next? What is upcoming for you that you want to share?

TR: There are a couple projects I'm working on—none of which I'm allowed to share at this moment—but I'm developing a few exhibitions for the coming years. It's a really exciting time to be at the Albright-Knox. We're all thrilled about Albright-Knox Northland, our temporary project space opening in January 2020, and what that space will allow us to do. We're also excited about our campus development and expansion project, and what the renovated spaces and the new building will allow us to do. Because we are going to have so many new opportunities, it's a great moment for us to step back and think about our vision and our mission, and what we’re going to do with the opportunities presented by these new spaces. While I'm really enjoying planning my personal projects, I'm also really enjoying getting to play a part, however small, in a larger dialogue about the future of the Albright-Knox and of art in Western New York.

“...in this moment, feminism is being reinvented, and that includes motherhood, too.”