Everything Looks Distorted Already: Joan Linder Interviewed by Becky Brown

Published in May, 2020 in the early days of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Issue 3 of Cornelia was virtual only.

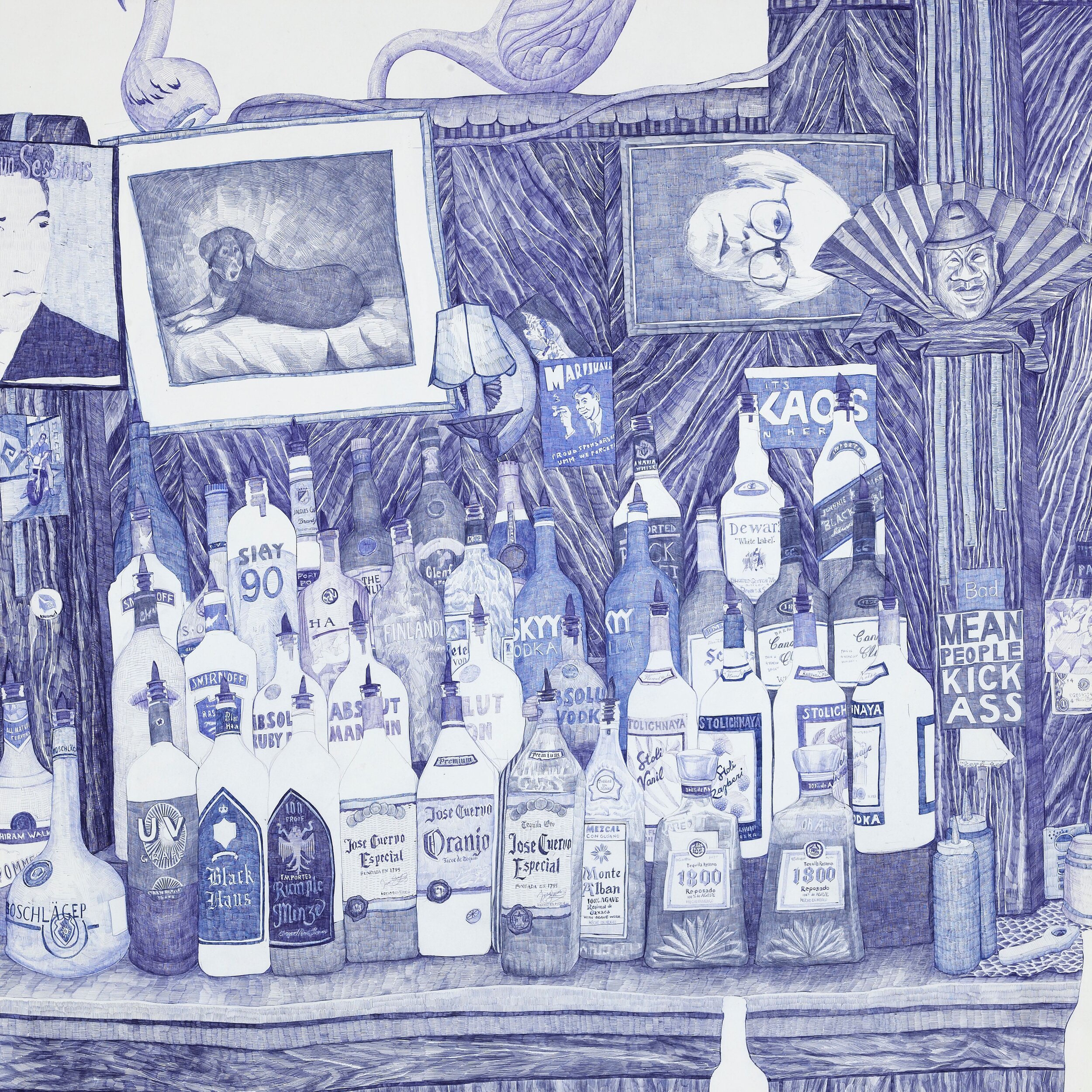

Brood, a solo exhibition of new drawings by Joan Linder at Nina Freudenheim Gallery, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Nando Alvarez-Perez.

Joan Linder’s exhibition Brood at Nina Freudenheim Gallery (March 6th–April 17th, 2020) was the last public display of artwork I saw in person, and I’m grateful I did. Art is about physical presence to varying degrees, but Joan’s work has a particular investment in material and scale; much of its power (and pleasure) is found in direct encounter. I met the artist last year when I joined the University at Buffalo Art Department. Since then, I’ve spent time with her drawing Don’t like country music? (an excerpt from The Pink (2007), a 1:1 scale drawing of The Pink bar in Allentown) that hangs in our department office, relishing its density of tiny ball-point pen lines, as well as the intimate view it offered into the culture of my new home, the city of Buffalo. I’ve also participated in an informal “drawing club” with Joan, drawing alongside her over whiskey and chocolate, and watching those tiny lines accumulate. I was thrilled to see this formal presentation in early March, bringing together four subjects in three series of small-scale drawings and one artist’s book. Joan’s work is among the many things I look forward to encountering face to face, at close range, when such encounters are safe again.

She and I talked via Zoom on May 28th 2020, and the below interview has been edited for clarity.

Becky Brown: The show Brood brought together different kinds of subjects, and I started off thinking: how do these things connect? I don’t land in one clear place, but I feel invited to test out different possibilities.

Now I realize one could say this same thing about your practice as a whole–a wide range of subjects, relationships and potential connections. Can “Brood” be seen as a microcosm of your oeuvre?

Joan Linder: Maybe. In the early 2000s, I did shows that made different connections between iconic imagery, and Brood does the same thing, except through series. One show at Mixed Greens included bound figures–this was when the whole Abu Ghraib situation was unfolding. I drew the rope, life-size, but I took the bodies out. Then in another room was this giant drawing of shelves of canned food in my parents’ basement. And there was a golf cart, and a soldier fully-outfitted for war in Iraq. So I was thinking about effects of war domestically, and power, and who’s making decisions (the guys in the golf carts?), and that was a show.

I had another show Of Bodies and Buildings (2007)–institutions of powers drawn in a wonky way, like the U.N. or the Department of Energy, mixed with tied-up bodies. Things were shifted around and recontextualized. “Brood” felt like I was doing that again–making different combinations.

BB: Rather than one show on one subject, like Project Sunshine (2017).

JL: Exactly, or The Pink. The egg cartons were about fertility, and I started them five or six years ago. They’re such strange containers–intersections of food culture and reproduction, and I was thinking about menopause, and the egg carton with one or two eggs left.

Joan Linder, wegmans grade aa, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

BB: Right–while we can buy as many cartons as we want, the viable eggs in our bodies are limited. But I also see them as everyday objects.

JL: Yes, they’re delightful as objects. And in capitalism, we have this insane variety, and everybody is trying to sell us something, and what are we buying into? The picture of the family on the organic egg carton? Does it say “happy hen?” Or is it Styrofoam, and you wouldn’t buy Styrofoam, but it’s pink and that’s fun to look at? How does packaging reflect personal identification and choice?

BB: Right–and how does it connect to what’s inside?

JL: The egg cartons and the tissue boxes were similar in that sense–outside vs. inside. At one point, drawing the tissue boxes, I was thinking, “tissue box designers actually have a larger audience than I ever will…” You look at these designs, and they’re ubiquitous and always changing…

BB: They’re almost like wallpaper…and there’s that complete disconnect between the design and the tissues. Usually packaging bears some relationship to its contents, but not in this case… And the different kinds of designs align all too well with the painting tradition–landscape, flora, abstraction and portraiture (maybe less common, but we have Santa!) Perhaps the disconnect between image and support reinforces this connection to painting…

JL: Yes, it’s truly a painting! The other thing I love is, it’s all paper–I’m making a painting about a painting that’s on paper, on paper, that houses a paper that is used to collect body fluids…I like the idea of variation, that everything is the same but different–we’re progressing, and we’re not progressing. That spiraling model of time.

I like to look at things, and I like to render them. But it takes me a long time to land on subjects that resonate.

BB: Right–once the subject is chosen, you’re free to render. What happens for you cognitively, or emotionally, in the process of rendering?

JL: I just enjoy when something pops into illusion, from abstract to representational. That’s why I don’t do conceptual art…

BB: The thrill of getting it right. So what about the logistics of it–the small-scale pieces you’re doing in the studio vs. drawing on-site?

Joan Linder, zig zag, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

JL: I went to the Love Canal site on and off over a couple of years. I would go for about three hours at a time, in the summer, and I would listen to the radio. Another series that’s interesting in terms of site observation are the life-size trees. I drew the first at Yaddo–I thought, why am I in my studio, it’s beautiful, and there’s a beautiful old tree…so I unrolled 3-4 feet of paper at a time, put board underneath it, sat outside…There was one tree I did not do from observation, and I think it’s terrible…And for the drawings of New York City, I sat outside my studio in Dumbo, and I’d get a lot of attention from passers-by…

BB: Like Rackstraw Downes, out there with the easel…

JL: I love his work. He came and talked at Columbia when I was a student, at a time when people weren’t talking about observational painting.

BB: There’s a video of him painting under a bridge–he’s representing the space, but he’s also inhabiting it, and that becomes part of the representation. I think that’s true of your work too. And maybe it’s the reason I started thinking about documentary filmmaking…

JL: Yes, I used to write about my work in terms of documentary, and I lived with a documentary filmmaker for six years, and was a producer of Call it Democracy, a film about the 2000 election. I think about scribing as slow documentary. Errol Morris’ 1997 film Fast, Cheap & Out of Control got me thinking about separate, iconic things being put together.

But sometimes it takes a circuitous path–I visited the anatomy labs at UB for years to draw the cadavers. I spent an enormous amount of time in the space; I audited gross anatomy. But I discovered that the cadavers weren’t the most interesting thing there. It was the culture that I observed during this sociological study. The drawing was just the excuse to be inserted into a place. So after four years there, I decided to make a drawing of the lab offices.

It was the same with The Pink. I had spent a lot of time at the bar, and when I came to Buffalo, I wanted to make a drawing that was iconic, about the city. At first I thought it had to be Niagara Falls, and I couldn’t wrap my head around it. I struggled on that for about two years, and then realized “it’s The Pink!”

BB: So you took a series of photos?

JL: Hundreds of details. Because I could only get about 5 or 8 feet back from the bar; and it smells.

BB: Both The Pink and the anatomy lab project make me think of the filmmaker Frederick Wiseman in particular. Like you, he has taken on a massive range of subjects, and shoots an enormous amount of footage that he slowly whittles down to a final film. He did one about a welfare office and said something like, “whatever happens in that building is part of the story.”

I thought of that with many of your projects–how the boundary is the anatomy lab itself, and the unexpected things you observe there. And as with Wiseman, it’s always a story of an institution. You take up something as personal (or private) as your kitchen sink, and as political (or public) as Love Canal. You explore an institution of scientific research in the anatomy labs; the “institution” of the art world in the series of artist resumes; or the “institution” of motherhood as seen through baby products.

JL: Yes, I’m always thinking in terms of genres or concept threads. There are about five things I’m interested in that I keep cycling back to. Usually it’s related to family; to feminism or women’s work or labor, equity; and there are themes of war, and trauma of war, and death drive, and the banal horror of power. And that dovetails into technology and institutions…

BB: And you say you’re not a conceptual artist!

JL: But the thrill for me is in making Santa’s beard look good…

BB: But that’s a way of getting at the banality of power, right? It’s in the documents from Love Canal that you reproduce, or in endless meetings at a welfare office–paperwork and bureaucracy.

JL: Yeah, that’s the conceptual hope. It gives me a chance to learn–whether it’s copying documents so I’m reading them more closely, and the excitement of the illusion “oh my god it’s not a xerox, it’s a drawing!” Maybe I’ll get somebody to read that document, and then it’s an entry point.

BB: And calling attention to all the levels of mediation, which are inherent to any search for truth–scanning, to microfilm, to printing, to drawing. So much reproduction!

JL: And different kinds of technology, and materiality. Right after graduate school, I started painting xerox machines. I read Walter Benjamin, and I was part of the whole “painting is dead” conversation, and I thought, “I’ll paint the copier!”

BB: And you did a lot of them?

JL: It was my first endless series–I swore I would be the Rob Ryman of xerox machines. I made about 10, and then moved on. But there has been a thread of these produced objects about technology or manufacturing. The tissue boxes relate, because they’re also about paper and copies.

The document drawings are also related to the copiers, because I became the copier.

BB: Yes, you replace the machine, instead of the machine replacing you. I see you playing the role of copier across your entire practice too, with all your subjects!

Can we return to connections between subjects in Brood?

Joan Linder, the pink (detail), 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

JL: I was thinking a lot about springtime and death. The egg cartons were women’s work, nourishment, menopause and empty vessels, and the tissue boxes were allergies and sadness and mourning a loss. I was also thinking about the egg cartons being designed to transport these fragile eggs compactly, and they precisely resemble the diagrams where you select your airplane seat–the same little rows. So, packaging people and packaging eggs, and birds make eggs; and airplanes fly, and birds fly. Except when we’re in flight, we’re sitting still in our seats. I was circling around all those things, and the title was a way of pulling it together.

BB: Yes, the brood is a family, and what constitutes a family? In another strange coincidence, there is a scene in Errol Morris’ film The Fog of War (2003), during Robert McNamara’s early career at the Ford Motor Company. To build safer cars, he uses egg cartons as an example of packaging built to protect its contents. But there are these dramatic, staged scenes of egg cartons slamming onto the floor and breaking. Morris often includes reenactment in his films, as though we might understand something better by playing it out again.

I see your document drawings as a form of reenactment too. Morris describes truth as a process of investigation, as opposed to a clear endpoint. Does that resonate with you?

JL: Definitely. I go to a place and observe, not knowing exactly what I’ll learn. But often, I’m a participant as well as an observer. This is true of the airplanes, in which I am also a passenger, and of The Pink.

BB: But you weren’t a participant in research on cadavers, you were an outsider…

JL: In a way, but I had access because I am also part of the institution. And like any institutional space, it was super-intimate–pictures of people’s kids, gag jokes. But there’s also a New York state license for handling dead bodies. It became a communal portrait of a space that jammed up personal and institutional things…I guess that is my perception of truth. It has all these weird intersections that you wouldn’t normally see.

BB: We talked about Rackstraw Downes; Dawn Clements and Toba Khedoori are other artists that come to mind. They all share with you a faithfulness in how they represent reality–true to life, without overt stylizing or distorting. In recent contemporary painting, there’s been a real return to representation, and it’s mostly human bodies, all uniquely-distorted. You avoid that–why?

JL: There’s two things going on there. One is, everything looks distorted to me anyway. And my work has gotten less and less distorted, because my hand-eye skills have gotten more refined…

BB: Yes, but you’re in control–I mean, Nicole Eisenman isn’t making her figures distorted for lack of skill…

JL: If I’m drawing a natural subject, it doesn’t look distorted. With a tree or a bird, the illusion is much more complete. Because in biology there is more wiggle room, or asymmetries. But in manufacturing, there is less asymmetry. Things are more perfect. My early drawings were covered with splatters…most of them were done with pen and ink, dipped pen, and there are really wonky lines…you can see some of that in the egg cartons, but I’ve gotten tighter. I never try to distort on purpose…For me, that’s always felt really contrived.

BB: Yes–truth is stranger than fiction!

JL: But Vija Celmins’ work is far tighter than mine…

BB: Right, you’re not doing photo-realism–that’s an important distinction. You allow distortions that happen naturally in the process, but you’re not setting out to make the eye gigantic, or the faucet into a snake… Our contemporary moment feels like a new Expression, a Neo- Neo-Expressionism!

JL: I think that’s just pushback against the screen. Everybody is craving a feeling of authenticity or hand, or material; and for me, subjects don’t need to be distorted to achieve that.

BB: Lastly, I want to ask about projects currently underway. I’ve seen you making drawings (and sometimes watercolors) during faculty meetings, and you attend a large quantity of meetings as department chair. Do you plan to assemble these works into a future series or exhibition? I imagine that being a very powerful portrait (or document) of an institution.

JL: The airplane book is one of three books in development. The other two are meetings and Skype interviews. I was thinking about middle management…the university institution has been really interesting, and I have about 500 projects I want to do that I can’t get to because I’m participating…but I’m excited about the book format.

BB: I love that the book creates sequence, and demands duration…and it’s also filmic.

JL: Yes. I have some working titles: for the meetings–“minutes,” or “excellence.” And the Skype interviews, I’m thinking of calling “opportunities.”

BB: That’s great–it goes back to the power dynamics running through many of your projects–with every “opportunity,” there is hierarchy…

Becky Brown is an artist and educator.