Ja’Tovia Gary at Memorial Art Gallery

by:

Emily E. Mangione

Published in May, 2020 in the early days of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Issue 3 of Cornelia was virtual only.

Ja'Tovia Gary (American, b. 1984) Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE), 2017, single-channel video, HD and SD video footage, 1920 x 1080, 16:9 aspect ratio. Memorial Art Gallery, Marion Stratton Gould and Herdle-Moore Funds. Still courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. © Ja’Tovia Gary.

In the beginning, we were meant to be gardeners. We were meant to stride across or lounge on verdant grounds like Ja’Tovia Gary does in her Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE), 2017, recently on view at Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery. This is what it looks like to embody the confidence that comes with knowing one has an unalienable right to inhabit a place, to be secure in one’s bodily and spatial sovereignty. With this powerful freedom came the understanding that we would care for the land that would in turn care for us: “The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep . . . every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” growing within its borders (Gen. 2:15, 9). Post–apple imbroglio, this relationship sours; the first couple is told: “cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Gen. 3:17–19). No longer gardeners, we are condemned to subsistence farming—to needing constantly to work, to exploit, to enact violence on a land that we have forgotten once cared for us. Of course, the most powerful among us have historically sought out proxies for this punishment, serfs and slaves to shoulder the toil so that those wielding power might eat of the ground without the whole “sweat of your face” bit.

And so the earth becomes subject to division: arable lands worked to produce the species-sustaining plants of the field culled from ever-diminishing swaths of wilderness. Gardens, those purposely purposeless plots set aside for pleasure alone, are now not a right but a privilege. The bounding, both spatial and bodily, of the postlapsarian garden is built into its very etymology: keep following the twisted roots of the modern English word and you find the Old Saxon gard “garden, dwelling, world,” Old High German gart “enclosure, circle, enclosed piece of property,” Old English geard “fence, enclosure, dwelling, home, district, country,” Old Frisian garda “family property, courtyard,” and perhaps the Indo-European ghortos “enclosure.”

View of “Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE),” 2017.Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester. ©Andy Olenick, Fotowerks, Ltd.

It is into this conversation about who determines the limits of these enclosures and which bodies are permitted inside that Gary offers her remarkable, devastating, and utterly necessary suite of films based on footage created during a 2016 Terra Foundation Summer Residency in Giverny, France. Over the course of that summer, a contest over the right to being in space would come into fatal focus back in the United States. June 12: a man armed with an assault-style rifle kills forty-nine and injures fifty-three patrons at Pulse, a LGBTQ-centric nightclub in Orlando. July 5: in the parking lot of a convenience store in Baton Rouge, police pin to the ground and shoot Alton Sterling. July 6: Philando Castile is shot during what should have been a routine traffic stop in Falcon Heights, a majority white suburb of Saint Paul, Minnesota.[1] Gary witnessed this all from afar, against the background of modern art’s most famous gardens. She recounts, “I’m in this garden in northern France, in the lap of fucking luxury, losing it a little, no shade. I’m the only Black person there. I was feeling my own body’s vulnerability. When people ask me what this is about, I say it’s about Black women’s bodily integrity, or the lack thereof.”[2]

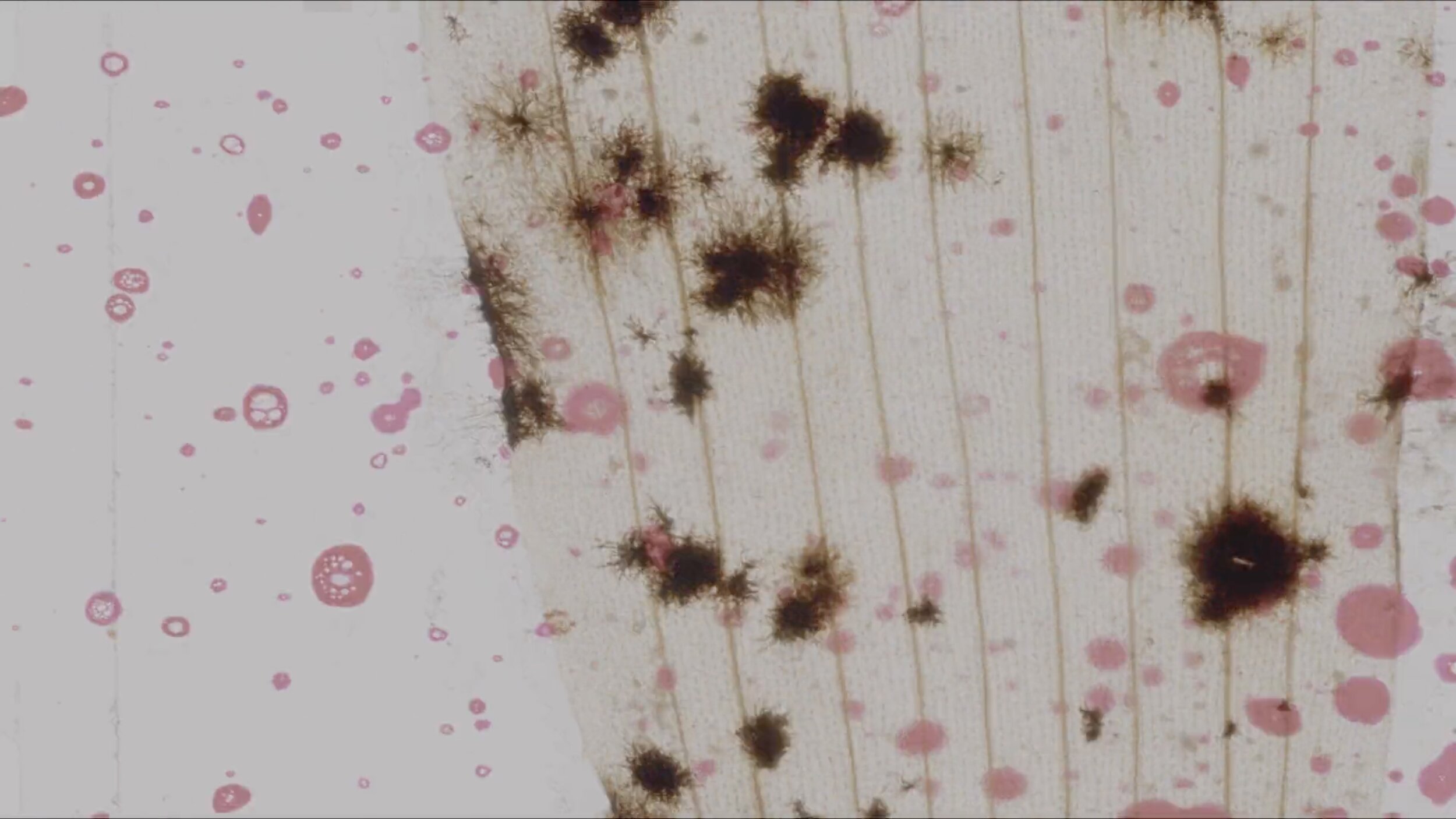

Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE) is one of the earliest of Gary’s ongoing body of works stemming from this experience.[3] The artist, who has admitted to being less a director who edits and more an editor who directs, here grafts together a number of different visual and audio components into a symbolically dense six-minute collage.[4] The film begins with imagery Gary created at Giverny: vibrant close-ups of flowers and other verdant plants interspersed with medium and long shots situating the artist within the gardens. She is a mercurial presence in this landscape, alternatingly framed in the center of the image or just slipping in and out of visibility among the greenery. At key points in the video, her face or entire body are circumscribed within a series of frames installed on the wall behind the projection, suggesting a comparative dialogue between Gary’s reimagining of the aesthetics and stakes of representing black womanhood and the way bodies such as hers have been treated in the traditions of Western art history.[5] Periodically we are shown the original artistic occupant of these spaces in excerpts from Ceux de Chez Nous—conventionally translated as Those of Our Land in a suggestive collision of home, land, and sovereignty—a 1915 film featuring Claude Monet painting en plein air at Giverny among segments dedicated to others of his fellow (aging, white, male) contemporaries at work. Abstract, solid-colored bars are juxtaposed with sections of camera-less footage Gary produced by fixing flora from Giverny to strips of clear films in passages inserted at rhythmic intervals like so many organic test cards. Initially overlaying all this footage is the distinctively thick, deep timbre of Louis Armstrong’s La Vie en rose as remixed by Norvis Junior; repeatedly, Armstrong asks us “to hold me close and hold me fast” in “a world where roses bloom.”

Ja'Tovia Gary (American, b. 1984) Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE), 2017, single-channel video, HD and SD video footage, 1920 x 1080, 16:9 aspect ratio. Memorial Art Gallery, Marion Stratton Gould and Herdle-Moore Funds. Still courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. © Ja’Tovia Gary.

The request becomes hauntingly tragic when juxtaposed with the final two strands of footage Gary weaves in: a recording of Fred Hampton, in which we see and hear him articulating fragments from an argument for the importance of education, intercut with excerpts from the livestream captured by Diamond Reynolds in the immediate aftermath of the police killing of her partner, Philando Castile. In this pairing, it is worth recalling that, beyond the horrific circumstances of their deaths at the hands of the state, Hampton and Castile may be connected in the historical reckoning by a shared set of values by which they lived their lives. As a leader in the Chicago branch of the Black Panther Party, Hampton was instrumental in organizing daily political education classes and a free breakfast program, and as a cafeteria supervisor at the J.J. Hill Montessori Magnet School in Saint Paul, Castile was well-known for paying for the lunches of students who couldn’t afford them or were already in debt for past meals—recognizing, as Hampton had before him, the deep connection between food security and the ability to participate fully in the education system.[6]

The Hampton footage is largely divorced from its audio track, but the Reynolds recording abruptly and insistently stops the Armstrong audio track cold whenever it appears, positioned by Gary as a kind of break, violently distinct from the myriad others at play. Gary saves, to great effect, the only instance of diegetic sound in the film for the very end. An accelerating sequence of cuts and glitches within footage—Gary suddenly appears and disappears from the grounds at Giverny, her face and figure occasionally obscured by abstracted greenery—culminates in the artist, standing on the oft-painted footbridge crossing Giverny’s water lily pond, letting loose a sustained, piercing scream in a damning assertion of both physical and sonic dominion, refusing invisibility and silence.

For Gary, such archival and contemporary found imagery depicting the violence inflicted on persons of color opens up a conversation around “the state’s sovereignty on violence, and how repeated arbitrary violence has been used against Black folks in particular as a life-sustaining practice for the dominant culture.”[7] To resurface these images, however, is not simply to counter our troublingly persistent tendency to deny the lived present of historical traumas nor to offer the facile closure of performative atonement: “I really think about redefining forgiveness, because often times we’re told to be the bigger person and let things go,” she says. “I want to trouble that a little bit. Sure, you can let go of the anger, because the anger eats you, but that doesn’t mean everything has to be some sort of ‘kumbaya reality’. What you can cultivate, what I’ve been interested in cultivating, is compassion. The ability to see myself in the other and to see the other in me, and to see where our relationship, our missteps, our experiences overlap.”[8]

If we are willing to take up the conversation around the historical and contemporary policing of which bodies have the right to gardens, among other defined spaces, opened up by Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE), what should the contours of this conversation look like? Simply to aim for “truth” in making visible objective documentation of past and present harms or to seek a kind of “reconciliation” founded in a quietist model of forgiveness that means giving up all claim to requital seems wholly inadequate to this moment. Instead, as Gary suggests, perhaps the objectives of such a conversation are best framed in terms of a radical and courageous compassion, of meeting the gaze of others as fellow citizens and equal partners in the ongoing experiment we call civil society and unlocking the gates of our enclosures to them.

At the core of Gary’s project are questions of bodily autonomy and sovereignty: which bodies are granted the unalienable freedom of dwelling, of occupying prescribed places, of defining and holding their ground. Framed through the artist’s lived experience as a woman of color, sovereignty here is not a given thing but a kind of action, a doing, a production of oneself as the négresse impériale, as it were. It is a set of practices for holding space in the world for oneself that are either facilitated or hampered by institutional and state power. Such power is asserted in myriad ways materially, visually, and aurally as infrastructures both visible and invisible. To navigate even our most everyday spaces is to enter into constant negotiations with such structures.

How, then, should we think about the space of the garden? Is it possible to reclaim and reimagine this space not as an enclosure predicated on exclusion—racial, social, economic, gender—but rather a circle, a dwelling, a world-oriented toward healing and open to all bodies? After all, as scholar and cultural historian Saidiya Hartman reminds us, “care is the antidote to violence.”[9] We shouldn’t be surprised by the irresolvable contradictions Gary opens up by insisting on occupying space as a woman of color in a landscape exemplary of white male privilege just as we shouldn’t be surprised by the presence of black bodies, legally embracing their second amendment rights or otherwise, in public space more generally. And in Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE)’s amassing of disjunctive images and sounds we just may be able to see a path forward, tracing that arc of history toward a more equitable distribution of sovereignty for all.

Emily E. Mangione is a writer, editor, educator, and very occasional curator.

Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester

500 University Avenue

Rochester NY 14607

[1] In a related, if slightly orthogonal, development, on June 27 the Supreme Court decides in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt that a series of Texas abortion-related laws constitute arbitrary and unreasonable state usurption of the constitutionally guaranteed bodily autonomy and sovereignty of citizens. Perversely, these same set of issues have resurfaced at the Court this term in June Medical Services LLC v. Russo.

[2] Quoted in Jasmin Hernandez, "Artist Ja'Tovia Gary and Her Films Are a Force to Be Reckoned With," Cultured, February 20, 2019, https://www.culturedmag.com/jatovia-gary/.

[3] Buffalonians may recall Gary as one of Squeaky Wheel’s summer 2017 Workspace Residents, during which time she completed postproduction on the related Giverny I and Giverny II.

[4] Gary makes this distinction in Rooney Elmi, “What Happened When a Filmmaker Asked Black Women Whether They Feel Safe,” Hyperallergic, October 8, 2019, https://hyperallergic.com/519343/jatovia-gary-ciff-interview-giverny-document/.

[5] Gary coordinated with Almudena Escobar López, Time-Based Media Curatorial Assistant at the Memorial Art Gallery, to develop this aspect of the exhibition design specifically for the museum's installation of Giverny I (NÉGRESSE IMPÉRIALE); she suggested pausing the projection on certain stills and placing the frames in response.

[6] This legacy is continued today by the Philando Castile Relief Foundation, established in 2019 to assist those impacted by gun and police violence as well as students and families dealing with food insecurity and student lunch debt.

[7] Quoted in Elmi, “What Happened When a Filmmaker Asked Black Women Whether They Feel Safe.”

[8] Quoted in Allison Sanchez, "This Artist Is Shifting The Status Quo To Magnify Historically Marginalized Voices," Uproxx, May 24, 2018, https://uproxx.com/life/jatovia-gary-documentary-film/.

[9] Gary has recently reimagined Hartman’s comments, which come from her contribution to In the Wake: A Salon in Honor of Christina Sharpe held at Barnard College on February 2, 2017, as neon text in a recent sculpture, Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017), 2020.