Shawn Kuruneru & Walter Scott at Cooper Cole

by :

Margaryta Golovchenko

Published in May, 2020 in the early days of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Issue 3 of Cornelia was virtual only.

Shawn Kuruneru, Emanata, 2020. Installation view: Cooper Cole Gallery.

As I step into Cooper Cole, I feel an overwhelming sensation of lightness and openness that is partially conditioned by the physical space itself, with its white walls and bright lights. I’m reminded of the similarly white and bright simulation in The Matrix where Morpheus brings Neo to show him that reality is fluid, dictated by the mind rather than the body. This analogy, as well as the idea that the body is not as solid nor as “fixed” as we tend to believe, is apt for the two solo shows on display—Shawn Kuruneru’s Emanata and Walter Scott’s Extension of Doubt—which share an interest in exploring the process of constructing the self.

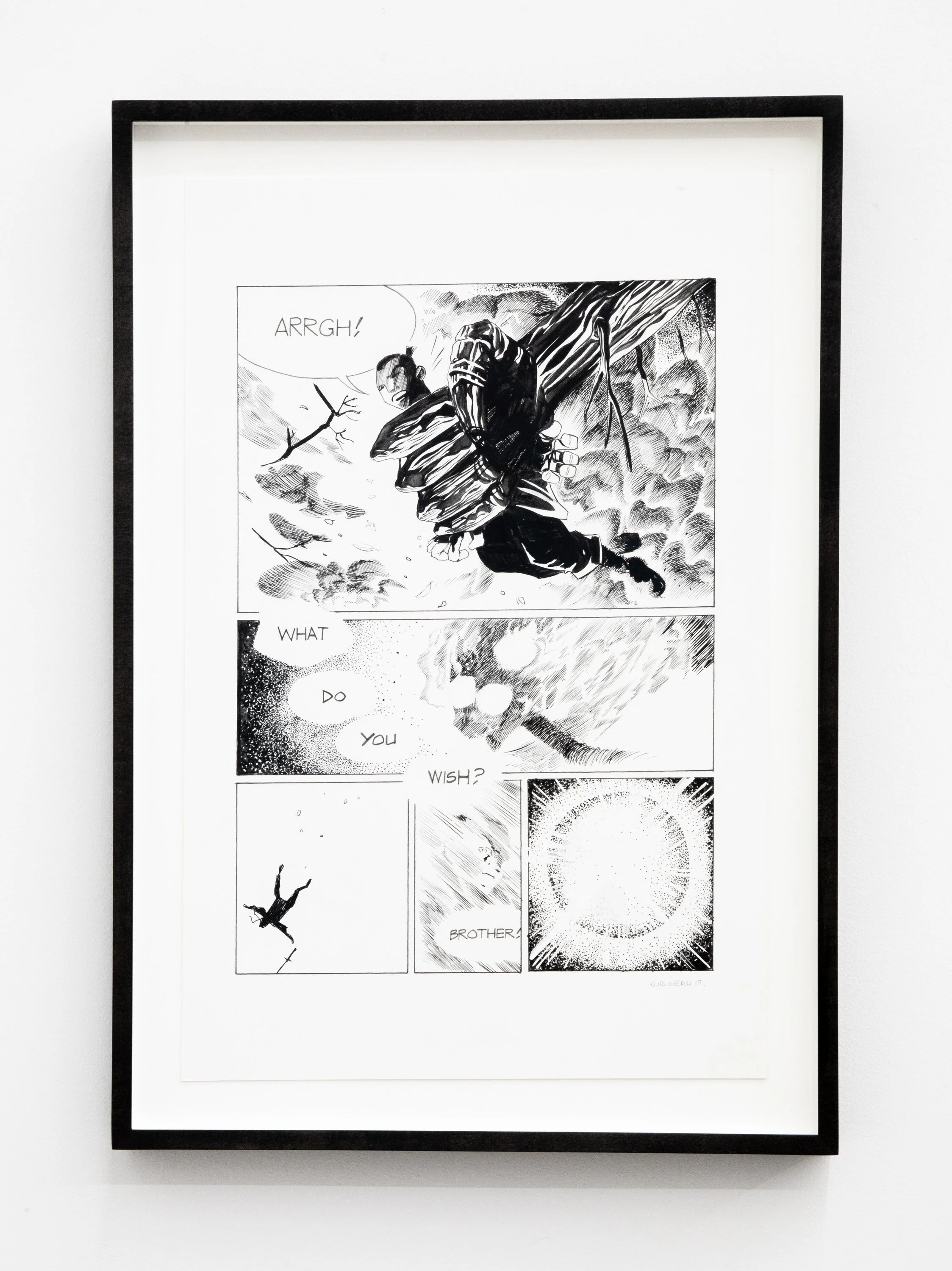

Of the two exhibitions Kuruneru’s comes across as the more physical one. Exploring the potential of drawing as a medium Emanata deals with not only the body and speech but also sense perception. The body’s physical agency and capabilities prove to be insignificant compared to both supernatural and natural forces, as the clenched figure in Fool’s Wish issue 2 page 12 (2019), from Kuruneru’s self-published comic, reminds us. Clutched by a giant hand that recalls a tree trunk, à la J. R. R. Tolkien’s Ents, the male figure can only yell out in discomfort before being dropped; his falling silhouette is shown in the bottom-left panel of the piece. Kuruneru plays with the format of the comic book and its ability to slice and divide individual identity literally with the help of panels. Although the corporeal body is only seen in its entirety in one panel from the pages on display, its presence is always felt, with thought bubbles an indication of the presence of a consciousness.

Shawn Kuruneru, Fool’s Wish issue 2 page 12, 2019. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

Kuruneru’s large monochromes from 2017 at once recall the color field painting of artists like Barnett Newman while his breathy application of paint and splatters of black also resonate with the large photograms of Wolfgang Tillmans. The results suggest sunlight streaming in through colorful curtains. A more recent series of black-and-white abstractions take the question of a dissolved corporeality even further by refusing to offer single, easily comprehensible forms. I spent quite some time in front of Kuruneru’s Emanata 1 and Emanata 2 paintings (both 2019), at first charting the outline of a skull and the profile of a soldier’s head, respectively, and then working hard to unsee these representational contours. More than merely an exploration of the elements and traditions of drawing, the diverse works brought together in Kuruneru’s exhibition make viewers aware of how the body is represented in different artistic traditions, from the mimetic approach in comic books to the deconstruction and abstraction in Cubist painting. The exhibition also surfaces how we have been conditioned to seek representation and meaning in the images we see, and the discomfort we feel when images deny us this opportunity.

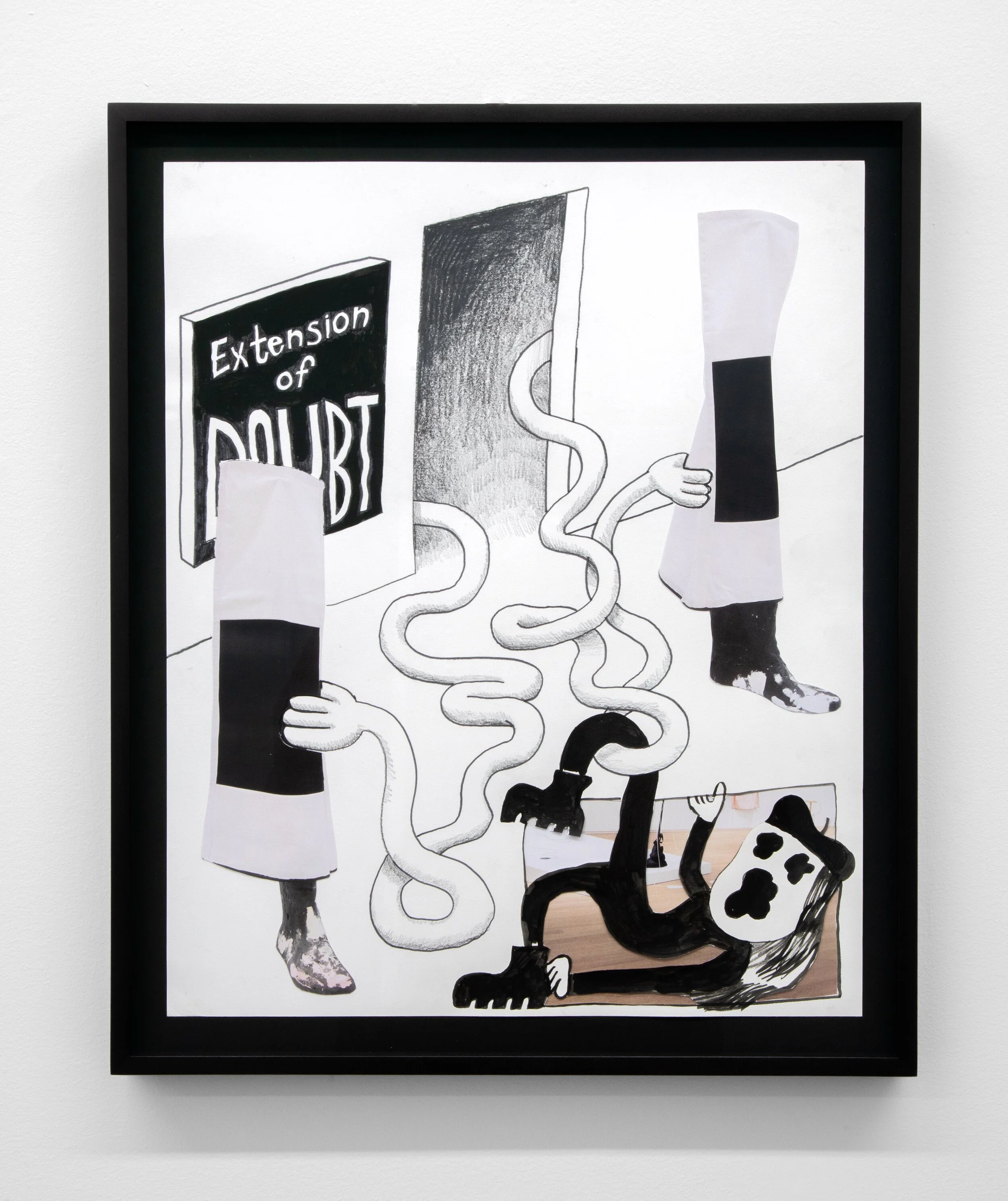

This willingness to let go of meaning holds true for Scott’s exhibition, Extension of Doubt, which forms the more subconscious, psychological half of the two exhibitions (a quality spatialized in its installation in Cooper Cole’s smaller subbasement exhibition space). The unifying thread through Scott’s work is a cerebral interest in exploring, in the words of the exhibition text, the “doubt that surrounds the art object during its display and creation,” yet the surreal and unsettling nature of his multimedia drawings begs a more immediate and emotional, as well as a more personal, form of engagement. The toxic greens and yellows in The Writer’s Table (2019) filled me with eerie discomfort even before I took in the representational content of the image, the ghostly expression and disproportionate features of the figure heightening my unease.

Shawn Kuruneru, Emanata, 2020. Installation view: Cooper Cole Gallery.

The semiautobiographical figures in satirical scenarios in Extension of Doubt feel like the art-world equivalent of quizzes purporting to reveal what magical creature or fictional character you are that many, myself included, have enjoyed over the years. In Scott’s works, these “archetypes” test the viewer’s preconception of what it means to hold yourself together and how this work is often conceived of as body-centric. In Reading Kathy Acker (2019), the twisting of the figure’s jelly-like limbs, as well as the violent red outline that surrounds her, contrast with the ripped-up pieces of text that seem to flock around her like birds, invoking the sensation of feeling torn apart on the inside and the sheer willpower that is sometimes required to prevent our body from following suit. Similarly, Spectre of the Subject (2019) touches on the fact that the mind and body often exist in different states when one experiences overwhelming emotions like fear or anxiety, resulting in out-of-body sensations that we are still often discouraged from showing in public, forcing us to become corporeal ghosts.

Kuruneru’s work occupies the main and upper floor of the gallery, whereas Scott’s is displayed in the basement. The two exhibitions are in dialogue with each other, working in tandem to examine how we think of our corporeal and psychological existence. The dichotomy of elevation and submersion, physically enacted in the visitor’s movements up and down stairs to view Kuruneru’s and Scott’s work, recalls the daily decisions we make in determining which parts of ourselves to make visible to the public and which to bury. While it may initially appear that the physical body is always on display while the mind is hidden, Kuruneru’s and Scott’s exhibitions disrupt this convention by reminding visitors that our identity, our bodies, and even our emotions are assemblages that we constantly add to and rewrite, and that acknowledging that we might not always be as in control of this process as we would like to be is its own act of subversion.

Walter Scott, Extension of Doubt, 2019. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

Walter Scott, The Writer’s Table, 2019. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.