Imagining Infinite Care

Sovereignty and Money in Kyla Kegler’s Mountains 2

Kyla Kegler, Mountains 2, 2022. Still from performance documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jonathan Paul Piret.

As we move into yet another new era of pandemic normalization in spring 2022, we find ourselves confronted by the eerie return of many of those issues troubling our day to day before COVID. Rising inflation, yawning inequality, and crappy jobs spur resentment across demographics; foreign sanctions translate into a domestic tax on anything touched by oil; and geopolitical brinkmanship bordering on a Freudian death drive challenges the throat-choking hegemony of the US dollar empire.

It is, perversely, an opportune time for Kyla Kegler’s Mountains 2, a “transapocalyptic soap opera about learning how to live while preparing to die.”[1] Two interrelated concepts, which have both played a significant role in world events over the last few years, shape, if at times latently, the meaning and making of the performance. As refracted through Mountains 2, changing notions of sovereignty and changing notions of money, particularly those derived from the heterodox school of economic thought known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), connect potential, but still largely unactualized, forms of common care and the capacity of financial resources to enable — or stifle — that care.

Kyla Kegler, Mountains 2, 2022. Still from performance documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jonathan Paul Piret.

The action at Torn Space Theater on two consecutive, and apparently quite different, February evenings picked up roughly where events of the first iteration, performed at Artpark as part of PLAY/GROUND 2020, left off. Kegler here resumes the role of the “Dictator (she/inner child/Taurus),” gently but sternly corralling the many performers on stage through a surreal stew of contemporary affects and anxieties, peppered with emotional elements drawn from their own lives. Fact, fiction, and narratives both personal and public crystalize in the form of the papier-mâché–masked performers. We meet “a Gen Z, preoccupied with trying to figure out ‘how to be a man’ at a time when the notion of Godly Masculinity is controversial,” “an ultra-high frequency empath and musical-cognitive-behavioral researcher who feels fundamentally misunderstood [and who] knows they are highly over-qualified and under-utilized in their role as Uni’s assistant, and have a combination inferiority-superiority complex because of it,” and “a heavy-weightlifter-addict turned self-proclaimed guru after going on an intensive 1-week detox Reiki training retreat in the Himalayas” under the allegorical appellations of “Horse Cosmic Matter (he/cosmic matter/Scorpio),” “Creature Comfort (he/they/Assistant/Society’s Death Doula/Capricorn),” and “Mole-Bear (Guru) #Blessed (she/they/Guru/Capricorn).” A sonic repertoire spanning the contemporary and historical, popular and avant-garde, helps to convey the tone for each character and mediates between the staged fantasy and our own inescapable reality.

Blurry dichotomies between puppet and performer, stage and audience, diegetic and nondiegetic worlds, irony and sincerity, and communion and disintegration characterize Mountains 2’s narrative details and four-part structure. In the Overture, Kegler as the roving Dictator commands the performers to the center of the stage and announces into her microphone: “So, this is the beginning scene where everything and everyone is connected and together in one molecule; and slowly and then very quickly everything is going to break away and be separate and alone.”

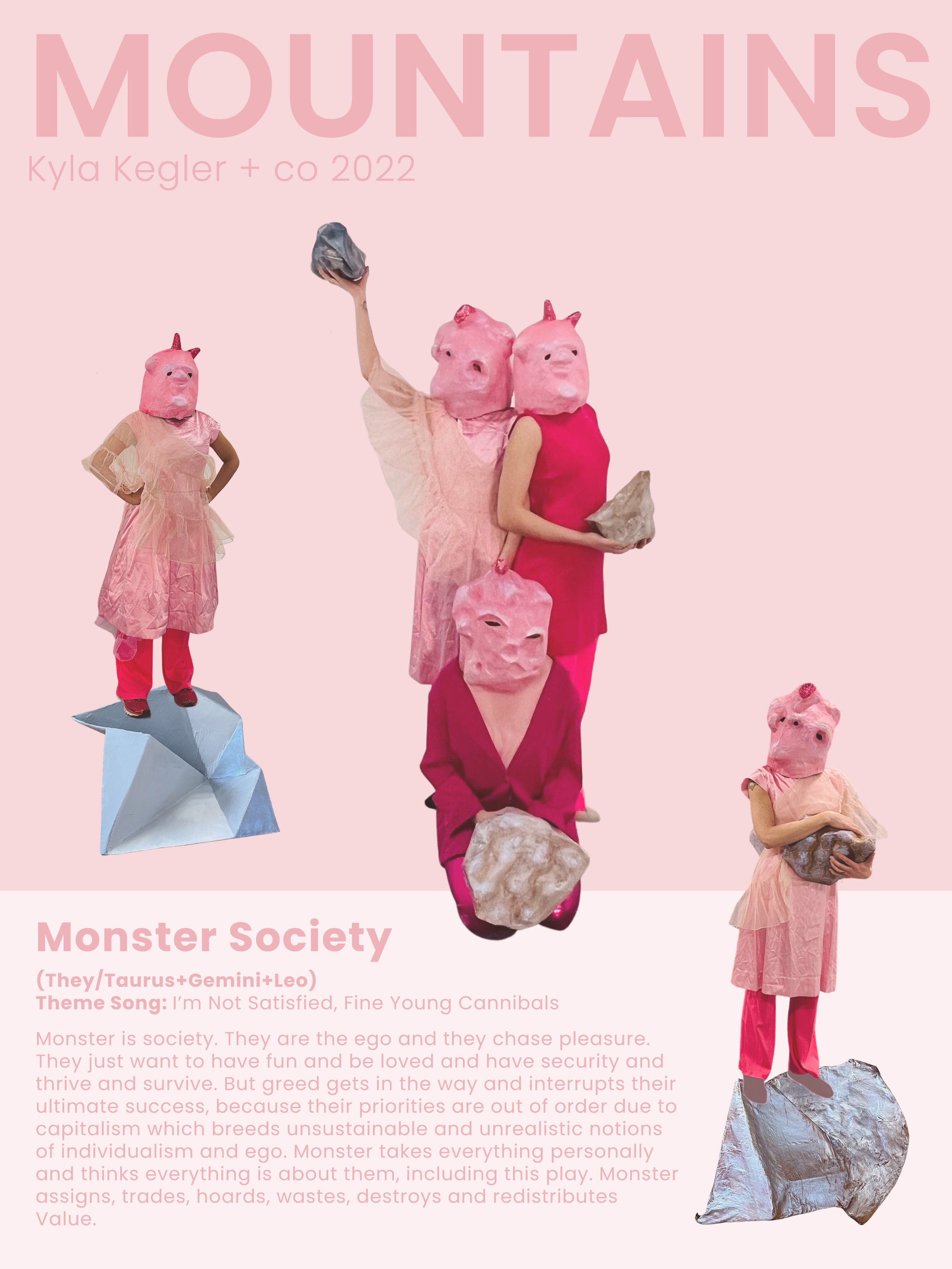

Kyla Kegler, Monster Society Bio Poster, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

And, indeed, throughout the first act’s first half, the Dictator shunts all of the characters, introduced along with their individual musical leitmotifs, into isolated, neurotic plots. Although purportedly inhabiting the early 2040s, the characters and their particular anxieties clearly draw from contemporary life. Ecological fears abound, and the pandemic is, of course, still ongoing. We see symptoms of the very lack of resources, connection, and care we experience in our own world wrack the bodies of these future beings. Kegler makes this sense of austerity explicit in the middle of act one when she auctions off one of the “value sculptures” created by “Monster Society (they/society/Taurus+Gemini+Leo),” a spooky sort of asynchronous triplet who sets such props in motion on a “Value Conveyor Belt/Treadmill.” It sold for $40.

Toward the end of act one, the characters YBB (she/star child/Virgo) and Horse Cosmic Matter share a dream about the kind of dance party, complete with all-too-real breath and sweat, that only existed “before the plague.” The act concludes with a fully clothed orgy orbiting around “Elephant Earth (she/Earth/Gaia/Sagittarius).” The contact-free yet apparently orgasmic experience kills all the puppets save for Creature Comfort, who guides their peers into the next life as a communal death doula. There is a recurring desire for communion, to return to the “one molecule” of the performance’s beginning, to find redemption in a caring community.

Act two meets these desires somewhat. The performers, perhaps chastened by the deaths of their puppets, try to work together under the Dictator’s direction. “Cleaning up the death,” in the Dictator’s words, they tidy the stage, arrange themselves single file, and sing Enya’s “Even in the Shadows.” Together, they make a landscape and do a kind of line dance to the cadences of John Prine. Prompted to “[be] aware of how much you’re giving and how much you’re taking,” they press their backs against one another and join hands.

In the penultimate scene, the Dictator guides the performers through a mantra addressing fears disclosed during rehearsals: “I deeply and completely love, accept, respect, and forgive myself, even with all of my problems, limitations, and challenges. . . . Even if I am not being cared for and am totally alone. . . . Even if I am being waterboarded. . . . Even if I am at the deepest darkest place at the bottom of the ocean . . . and I have the teeth-falling-out nightmare . . . and I am homeless . . . and I am a disappointment to my future children . . . and I have PTSD forever . . . and I’m not good enough and I’m a total impostor.” Symptoms of neoliberal austerity — particularly the privatization of care and aesthetic experience — pervade Mountains 2, but ultimately each performer, through the guidance of the Dictator, appears to come to terms with their fears and to point a way toward a potential ethic of sovereign care and alternative interdependencies. As Seth Tyler Black, who played “Cat-Dog Rainbow (fluid/rainbow/saudade/Capricorn),” wrote to Kegler after the performance, “Mountains was such a beautiful piece showcasing the different modes and approaches to connection that we all took while lost and trying to find ground to live during a pandemic.”

Kyla Kegler, Mountains 2, 2022. Still from performance documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jonathan Paul Piret.

Watching this all play out, I found myself unexpectedly returning to the opening line of Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology: “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.”[2] Schmitt then goes on to elaborate on this terse gnosticism, outlining what makes for the kind of emergency that demands exception to the constitutional order and who determines that this is so. Schmitt's Hobbesian and unabashedly authoritarian formulation speaks to a world where law seems to have a very limited power to curtail a sovereign's ability to act, and the values of democracy falter at cross-purposes with the imperatives of liberalism. [3]

Exceptions defined the lives of both Kegler’s Mountains performances and their progenitor. The pandemic’s forced cancellation of the 2020 summer concert season opened up an unexpected space on Artpark’s stage for Kegler’s first iteration. Some eighteen months later, Kegler found herself needing to negotiate with an unusual situation during the second evening of Mountains 2. Unhappy with the traditional theatrical trappings of the previous evening, particularly how the stage lights seemed to demarcate a boundary between performers and audience sitting in darkness, Kegler decided to leave the overheads on for evening two. This exceptional state, however, did compel an abrupt, destabilizing announcement that the performance is beginning now, has, in fact, already begun without our knowing it. Over the course of both evenings, Kegler the Dictator contends with a revolving door of emergencies: technology failures hinder and alter the performance, puppets seem unable to hear her commands, and the actors in their papier-mâché masks visibly overheat, tire, and require rest. That Kegler permits such pauses speaks to her own formulation of sovereignty: one that places questions of care at the heart of the political. In place of Schmitt and his dour authoritarianism, Kegler calls on the insights of generations of civil rights, feminist, and queer thinkers and activists who center care in their descriptions of bodily autonomy and positive personal freedoms.

During the Q and A following the performance, one audience member described the experience of Mountains 2 as “a gift.” Clearly, the surplus value created through Kegler’s production has little to do with profit but rather seems to enable caring, even therapeutic, interactions within a community. But such a gift — and any provision of care more broadly — never comes free. Unlike the cash-strapped original iteration of the project, Mountains 2 benefited from NYSCA funding for individual artists awarded through ASI WNY. Without any of the false propriety too often used to obfuscate interactions between art and capital, Mountains 2 frankly evinces the capacity of money to enable communal care, questioning what a society views as valuable and how it chooses to provision itself. One heterodox solution to the latter dilemma comes in the form of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Proponents of MMT emphasize that money is not a finite resource, requiring periodic regimes of austerity. Money is, and always has been, a creation of the state, not barter relations. “Its function as measure, meaning, and value derived first and foremost from state authority,” Scott Ferguson writes in Declarations of Dependence: Money, Aesthetics, and the Politics of Care. “The primary ‘law’ that regulates the money relation is that which is legislated and enforced by human governments.” [4] Currency-issuing governments are in essence already in the business of creating money out of thin air every time they authorize federal spending.[5] A state with a high degree of monetary sovereignty can make as much money as it requires to provision itself since it simply cannot run out of a currency which it alone produces.[6] Money is, therefore, an infinite creative medium that can appear anywhere it is required, an on-demand resource not unlike the songs streaming from Kegler’s laptop in Mountains 2.

Kyla Kegler, Mountains 2, 2022. Still from performance documentation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jonathan Paul Piret.

Ferguson argues that MMT offers a way out of that hoary old dialectic between money and aesthetics, the idea that “money enslaves and the aesthetic saves.” Although anyone exposed to the economic realities of Renaissance patronage, the grotesqueries of contemporary art fairs, or the inexorable proliferation of vacuous “intellectual property” universes must on some level realize the absurdity of such an oversimplification, it has remained remarkably persistent in Western thought. The aesthetic, no less than money alone, has failed to save us. But only one of these things, history has shown, might be capable of redeeming the other. The idea that public money could and should make up for private capital’s lack of support to artists anchored the logic guiding New Deal funding for the arts. Kegler’s frank admission during the Q and A — that Mountains 2 was a direct response to the limited financial resources available for its first iteration that in turn limited its cast, design, and audience reach — is a reminder of the power of such programs. Nearly a century on from the heyday of this funding, it has become clear that money still acts as a sort of “proto-aesthetic” field or minimum floor for aesthetic and sensory experience: defining the limit of not only what is possible but also of what is imaginable.[7]

When Carl Schmitt wasn’t busy expounding on authoritarianism in theory, he was actively involved in its expansion in reality, providing a quasi-judicial framework for the formation of the Nazi state. As Political Theology entered its second edition in 1934, another German thinker, already in exile, was also exploring the limits of sovereign authority and the role of money in public life. In the epilogue to “The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin expounds on the impact of money held privately, hoarded, and spent on individual ends instead of deployed as a shared public utility. He writes (and it seems worth quoting in full in 2022):

“If the natural utilization of productive forces is impeded by the property system, the increase in technical devices, in speed, and in the sources of energy will press for an unnatural utilization, and this is found in war. The destructiveness of war furnishes proof that society has not been mature enough to incorporate technology as its organ, that technology has not been sufficiently developed to cope with the elemental forces of society. The horrible features of imperialistic warfare are attributable to the discrepancy between the tremendous means of production and their inadequate utilization in the process of production — in other words, to unemployment and the lack of markets. Imperialistic war is a rebellion of technology which collects, in the form of ‘human material,’ the claims to which society has denied its natural material. Instead of draining rivers, society directs a human stream into a bed of trenches; instead of dropping seeds from airplanes, it drops incendiary bombs over cities; and through gas warfare the aura is abolished in a new way.” [8]

Arriving at a time when the world is, without a doubt, in a state of multiple overlapping emergencies— disease, war, climate crisis, flabbergasting inequality — Mountains 2 reminds us that the work of building a society that nurtures human and nonhuman entities is essentially infinite; there is very literally a job for everyone. A caring sovereign, one that revels in the boundless capacity of money to account for the needs of every being on this planet, can direct resources wherever they are needed most: away from war, away from environmental degradation, toward care, and toward the public good.

[1] Quotations courtesy the artist unless otherwise noted.

[2] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 5.

[3] Recent relevant examples of sotto voce despotic tendencies in “democratic” regimes include the Canadian government’s brief freezing of protestors’ bank accounts under an expansive “Emergencies Act,” and repeated impositions on national sovereignty by those very actors — especially the United States and NATO — most vocally decrying Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

[4] Scott Ferguson, Declarations of Dependence: Money, Aesthetics, and the Politics of Care (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 54. David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years also explores the history of credit money in great detail.

[5] This is contrary to the “exogenous” theory of money creation, which understands money as an extant quantity that can be “variously recycled, expanded, or contracted,” and requires that taxes be collected first, before a government can spend.

[6] No, this does not mean inflation is not a serious issue, nor that taxes are unnecessary for a currency-issuing government. Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People's Economy is a valuable read on these and many more points.

[7] Ferguson, Declarations of Dependence, 94. In MMT’s framework, this bottom limit takes the form of a “jobs guarantee” under which the federal government would provide respectable, remunerated work to every person who wants it but cannot find it in the private sector. By acting as the “employer of last resort” and setting the absolute minimum wage, the government would force private capital to compete with the public market for labor, putting the “coercive laws of competition” to work for the benefit of workers.

[8] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn and ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Penguin Random House, 2007), 242.

Nando Alvarez-Perez is an artist and educator in Buffalo, NY. He is the co-founder of The Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art and editor of Cornelia Magazine.