Exploded iPhone Notes

Tara Fay Coleman on the Dialectics of Intimacy Culture

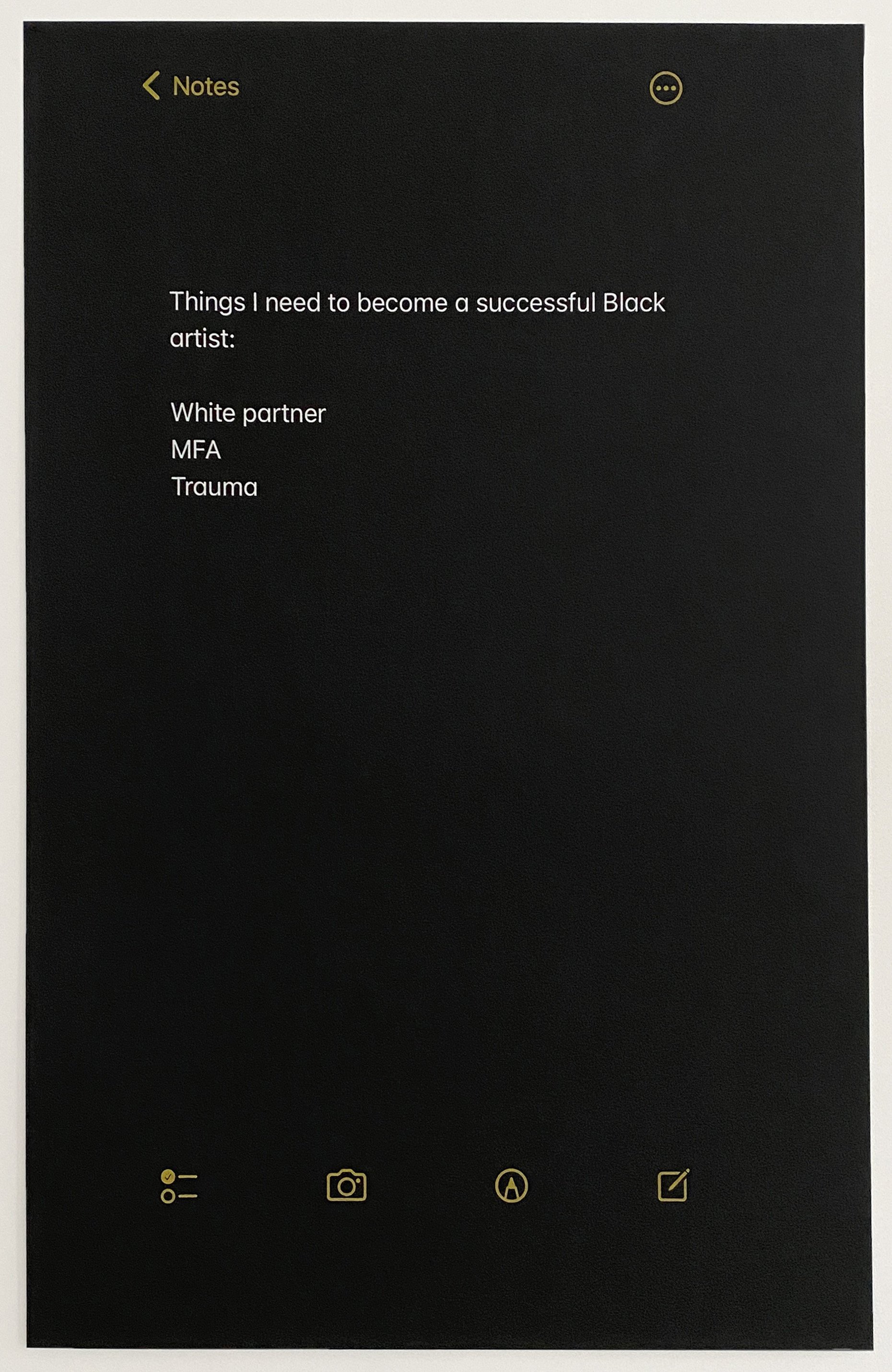

Tara Fay Coleman, iPhone Note (#9), 2022. Screen print on paper, 40 × 26 inches. Courtesy of the artist and here gallery, Pittsburgh.

The term “marginalia” typically refers to notes written in the margins of books. Historically, prior to their mass production, written works were cherished assets bequeathed to later generations of scholars and knowledge-seekers, and marginalia offered a means of transmitting thoughts and ideas to future generations — a fancy method of passing notes, as it were. While the practice of writing in books has become less ubiquitous, Buffalo native and Pittsburgh-based artist Tara Fay Coleman revives the practice for a contemporary audience in her first solo exhibition of text-based work, aptly titled Marginalia, at here Gallery in Pittsburgh.

Coleman’s work turns the notion of marginalia-inscribed books as collective material repositories passed through history on its head by making physical the most ephemeral, transitory, and quixotic of mediums: the iPhone note. Like many of us, Coleman writes dozens of notes throughout her day. Some are mundane — grocery lists, song lyrics, drafts of romantic texts — and some are more thoughtful musings on the state of the art world and her place in it as a biracial Black woman living in one of the most segregated cities in the Rust Belt. The exhibition at here Gallery brings these notes to life with uncanny verisimilitude. Iterations of the familiar black screen, with its white text and yellow accents, adorn the walls as a series of nine 40 × 26–inch screen prints, which at first glance look like monitors come to life. Upon closer inspection, the edges are softer, the surfaces textured where there was previously the uncanny smoothness of the screen. It’s a cheeky answer to a question that Coleman, as a conceptual performance artist, asks herself often: How does one transition conceptual art into a physical form adequate to its ideas?

Tara Fay Coleman, iPhone Note (#1), Screen print on paper, 40 x 26 inches. Courtesy of the artist and here gallery, Pittsburgh.

Coleman grew up in the predominantly Black East Side of Buffalo. Though familiar with drawing and painting, she wasn’t exposed to conceptual practices in art until she moved to Pittsburgh, where she began creating her own artwork. Pittsburgh allowed her to explore new elements of her practice, but it also spawned a feeling of relegation to the margins at the root of this exhibition. A Rust Belt city like Buffalo, Pittsburgh is even more racially divided and provides fewer opportunities for its Black residents, particularly Black women.

Marginalia presents an unabashed procession of the self-deprecation, isolation, and defensive humor that plagues many emerging artists alongside a scathing critique of the often insular, exclusionary, and precious nature of the art world. In iPhone Note (#9) (2022), Coleman sets forth the “three things [she] [needs] to become a successful Black artist”: a white partner, an MFA, and trauma. Much of the work expresses the isolation and sensation of being an outsider that Coleman explores in her other identity-based performance work. As a Black conceptual artist whose practice often explores motherhood, race, and gender, the artist frequently finds herself pushed to the outskirts of the art world. Although Coleman has had an impressive run both as an artist (she performed her 2018 hair braiding piece, Flow State, at the Carnegie Museum of Art) and curator, she stills feels as though she’s fruitlessly knocking at the gates of more sustainable support for her career; for instance, one museum that showed her work would not hire her as a staff member. In iPhone Note (#1) (2022), Coleman expresses some of this frustration through a “Checklist for a Black artist.” The refrain “Black woman/Black woman/ Black woman” punctuates a list of wry imperatives about opportunity, nuance, and diversity. The phrase reminds viewers that each of these clever, svelte pieces is actually a voyeuristic view into quotidian exasperations and disappointments jotted down with the same ordinariness as a grocery list. The final item repeats three times: “Lack of/Lack of/Lack of.” The exhaustion is palpable.

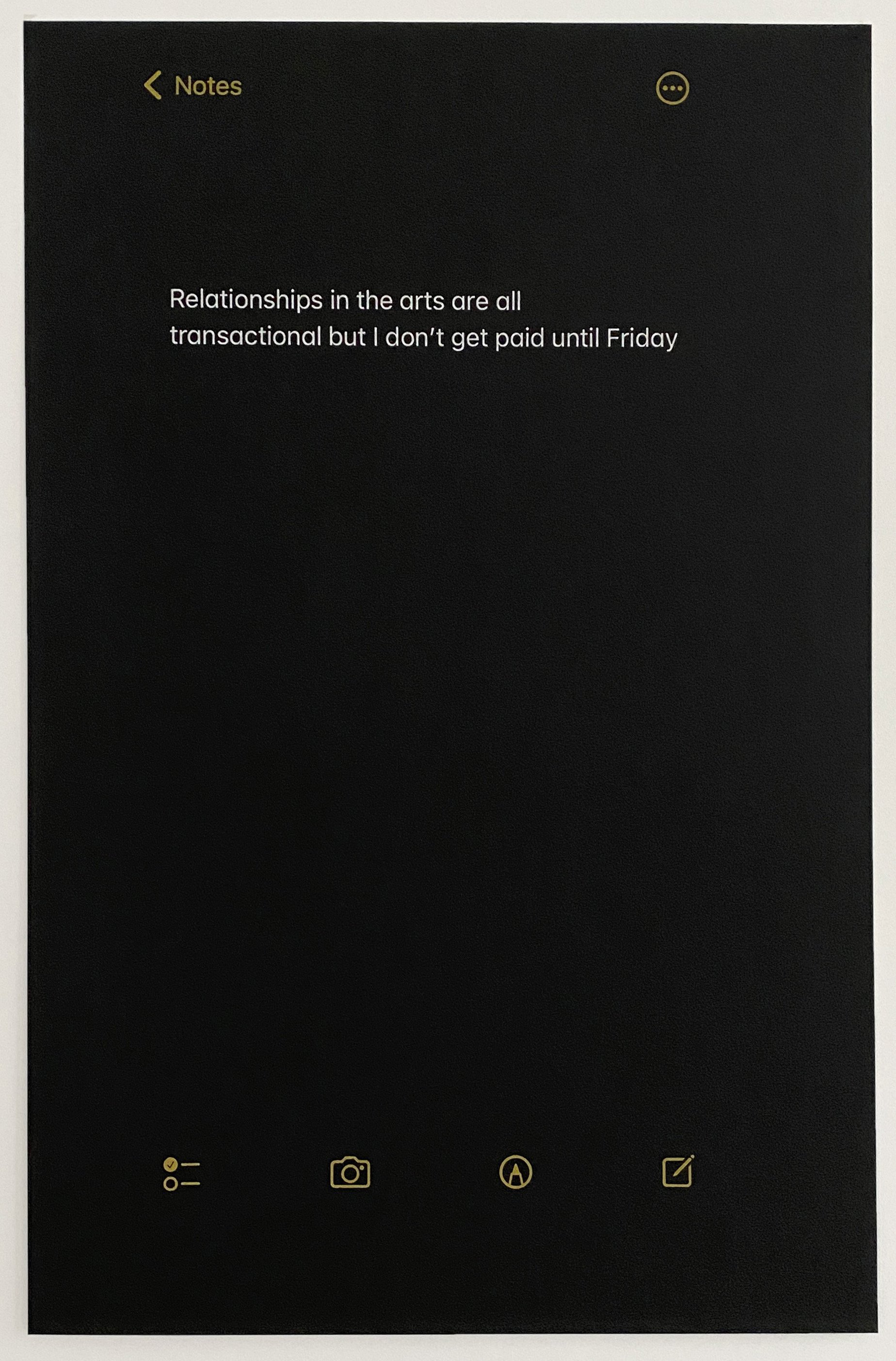

Tara Fay Coleman, iPhone Note (#6), Screen print on paper, 40 x 26 inches. Courtesy of the artist and here gallery, Pittsburgh.

The extremely intimate works in this show are also humorous, bleak indictments of shared frustrations with the impersonal and calculated expectations of today’s highly commodified art world. In iPhone Note (#6) (2022), Coleman deadpans: “Relationships in the arts are all transactional but I don’t get paid until Friday.” The artist has neither the time nor emotional energy to invest in the self- promotion and schmoozing it would take to lift her from the margins into the center. In another note, she lambastes the “tastemaker to gatekeeper pipeline” that keeps the arts scene insular and treats artworks as scarce commodities with inaccessible price tags, the ownership of which grants an ineffable cultural cachet.

Of course, Coleman is no mere sacrifice on the altar of a powerful predatory art market, and her commentary on the art world and its inhabitants is not unilateral; rather, it’s a complicated self-referential critique that acknowledges the dialectical relationship between the creator, the artwork, and the milieu of contemporary culture. Coleman implicates herself in the very culture she dissects; she meticulously prepares her prints in editions of three, ready to be sold. There is no “outside” to capitalism or its avatar, the “fine art market.” Coleman lays bare her complex status as both critic and organelle of the latter in iPhone Note (#3) (2022): “Curators are the new influencers (derogatory).” For an artist/curator, this is immanent critique, both earnest and self-satirizing.

Art theorist Boris Groys, in his essay “The Immortal Bodies,” posits that removing artwork from its everyday material context and ensconcing it in a cultural space of both physical and ideological preservation offers the artist some measure of immortality. For Groys, this is a kind of vampirism: not a truly vital life but an artificially prolonged post-death. It strikes me that this attitude is not part of medieval marginalia practices; though those scholars treated and preserved each manuscript as precious, it was in the spirit of the work’s contribution to a living community unfolding through history.

Tara Fay Coleman, iPhone Note (#3), Screen print on paper, 40 x 26 inches. Courtesy of the artist and here gallery, Pittsburgh.

So what is Marginalia’s relation to the “work of art”? How do Coleman’s acerbic notes fit into the long history of conceptual, text-based artworks, from John Baldessari’s 1971 dictum, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, to Juan Uribe’s 2015 charge, Art Always Imitates Previous Famous Art (2015)? Though Coleman’s work rhymes with the latter’s satirical comments on the commercialization of art, it seems to me that the pieces in Marginalia belong more to the world of traditional textual annotation. At first glance, the transformation of digital, portable iPhone notes into unwieldy “works of art” that hang on the gallery wall seems to resemble Groys’s description of the museum space, hung with the not-quite-living corpses of history. However, the rendering of these notes into real, physical objects creates a cognitive dissonance that makes the gallery experience laughable — literally “blowing up” notes that are usually private and mundane is funny! It eases the tension and worry of going into the gallery to experience “serious art” and demystifies the persona of Coleman as untouchable artiste, further nudging her to the margins of contemporary art’s self-aggrandizing gravitas. Even enlarged and printed, the images are not immortal or precious, and therefore do not need to be protected through institution or ideology. One can be yours for $500: a relatively modest price point guarding against the typical ascent of an artwork into the airy heights of financial speculation.

Tara Fay Coleman, Marginalia, installation view, 2022, here Gallery. Courtesy of the artist and here gallery, Pittsburgh.

What the works in Marginalia provide is a shocking, touching reminder that we are not alone in our fears, self-doubts, and frustrations. Like the notes in the margins of old manuscripts, passed from person to person, these iPhone notes create a sense of community and belonging. In this brave new world, art and commerce, vulnerability and aloofness, are not simple antitheses holding each other at bay, and contemporary art must acknowledge the intricate relationships like these that sustain cultural production. Coleman takes a common medium and, instead of elevating it to either “art” or a new Black art-historical archive, finds a route between the two that is darkly humorous — something new, something both tough and tender.

by Anna Mirzayan

Anna Mirzayan (she/her) is a freelance arts writer, poet, researcher, editor, and fat curator. She holds a PhD in Theory and Criticism. She is currently based in Pittsburgh, where she is the editor-in-chief of the Bunker Review and Operations Coordinator at Bunker Projects. Her poetry chapbook, Donkey-girl and Other Hybrids, was published in 2021 by Really Serious Literature. Her first curated exhibition, Soma Grossa, laid a groundwork for critical explorations by fat artists in the fine arts, and she wrote about the experience of being a fat curator at Hyperallergic. She is currently working on a solo sculptural show about fat suits with Canadian artist Zoë Schneider. She is interested in the intersection of fatness and curatorial/ artistic praxis, the history of radical fat liberation, and what it means to integrate the fat identity into political and cultural practices.