Alt-Arts: Spy Gallery by Margot Fabre

A series of profiles, written by Ashley Diana Culver, highlighting alternative art spaces in Toronto and the people who make them.

LungA School, 2024. Courtesy of Leander Albin.

Photo: Leander Albin.

It all began in a dream. Margot Fabre was on a spontaneous trip to London with her friend, the artist, writer, and DJ Akash Bansal, when this dream of publishing occurred.

“I woke up from this dream, and Akash was at the coffee shop already, and I was walking really fast,” Fabre says. “I was so excited to tell him about it. And then, I thought, ‘Okay let’s start a press.’ Akash and I started working on a magazine project that completely fell apart.”

While this initial attempt at publishing didn’t reach the publication stage, Fabre has persisted. Since then, she hosted six reading nights—each accompanied by a zine published by her Spy Press—curated an exhibition as Spy Gallery, and, most recently, organized a book fair.

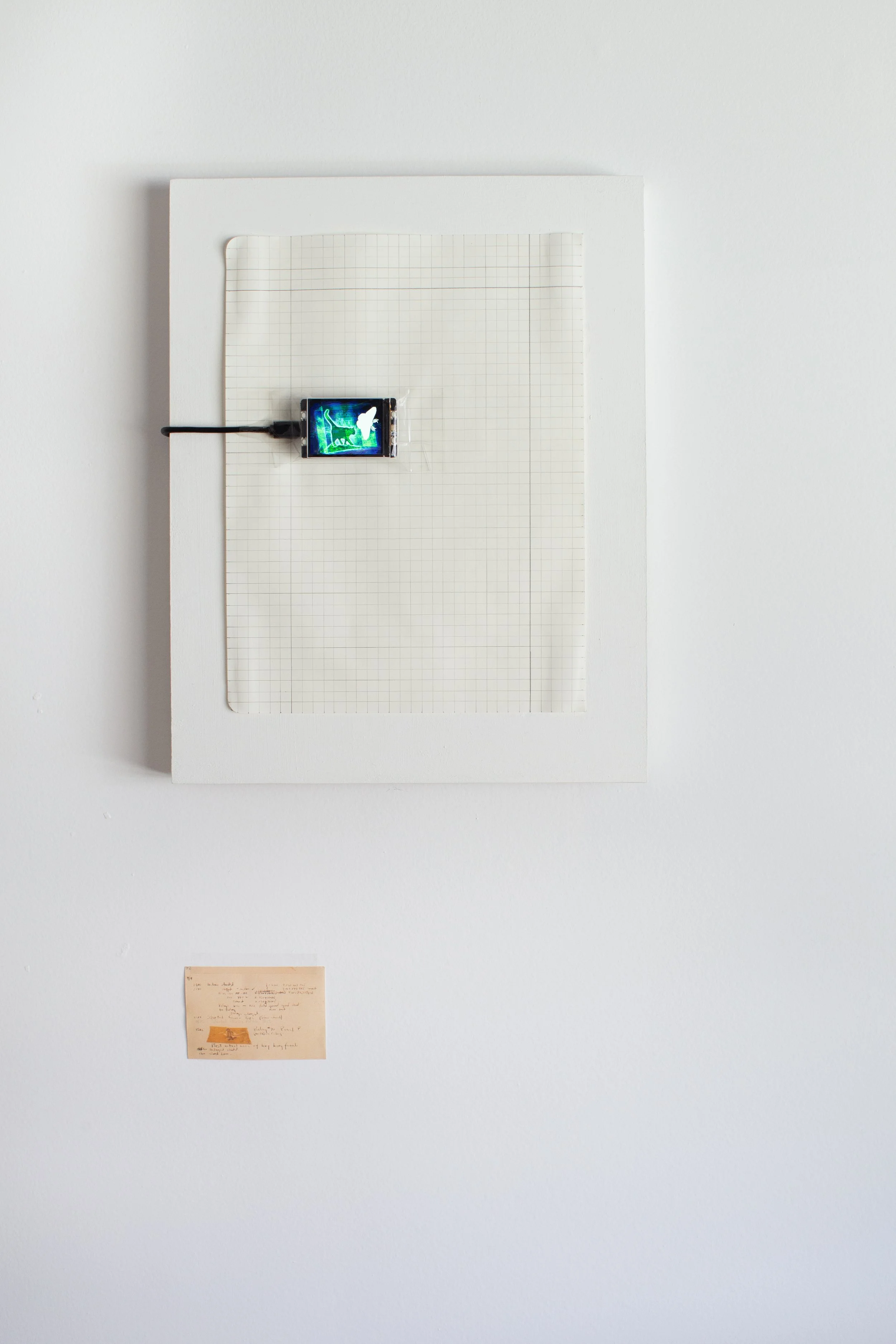

Nilou Ghaemi, LIVING ROOM, 2025, installation view, Spy Gallery. Courtesy of Nilou Ghaemi.

Photo: Nilou Ghaemi.

In April 2024, Fabre invited Jess Beketa, Seden Lai, and Sara Legg to her apartment for Reading night: 001. They sat on her bed and bean bag in her home at the time, a loft whose size and height earned it the moniker the tree house. Each attendee read a piece of their writing. This avoided any possibility of a passive audience. Afterward, Fabre collected all the texts and published a zine as “the physical record of the evening.” This duality of a private gathering available to the public in print has continued. Fabre maintains the original formula, but augmented more recent editions with themes (including Erotica?, Letters, and Texts with no ‘E’) and a larger number of attendees.

“Margot has a knack for collecting a wide range of people who might not otherwise have occasion to be in a room together,” says Cason Sharpe, who participated in Reading night: 004. “Even though everyone might not know each other, there’s always a spirit of generosity.”

Fabre was born in Toulouse, France, and moved to Toronto in 2016 for a nine-to-five job at a graphic design studio. She returns to her hometown annually and often stops in London on the way. For Fabre, the capital has become “a place that is familiar but foreign enough to romanticize” and “a liminal space where I can process and imagine what the future can hold.”

Shaheer Tarar, LIVING ROOM, 2025, installation view, Spy Gallery. Courtesy of Nilou Ghaemi.

Photo: Nilou Ghaemi.

It was at a dinner in London this past winter that the idea of starting a gallery occurred to Fabre. She was out with Marisa Müsing and Shaheer Tarar, Canadian artists Fabre befriended before they both separately moved to the United Kingdom. The trio discussed whether Fabre should take a year-long sublet posted by a mutual friend for a bungalow house in the Brockton Village neighborhood of Toronto. The house was more spacious than Fabre’s tree house, but the layout—two small rooms and a kitchen connected by a long hallway—was odd. By the end of the meal, Fabre resolved to take the sublet if the landlord permitted her to run a gallery in the front room. They also decided on an exhibition title and Müsing’s and Tarar’s participation. “It’s all a little bit serendipitous,” says Fabre, “And the project grows in different ways.”

“The idea came in Iceland too,” says Fabre. She was in Seyðisfjörður, Iceland, to attend LungA School, “an independent, artist-led institution and situation experimenting with . . . notions of aesthetics, learning, perception and good judgement.” She spent three months, from September to December 2024, living and eating and learning and making and being with twenty fellow students. “It was all really spontaneous and happening really fast in a way that was exciting. We would decide to do a show on the Monday and then put it up on the Friday,” says Fabre. “I felt inspired by this collective coming together, and I wanted to carry that energy to Toronto.”

Fabre attributes this surge of creative flow to the environment of the immersive school, but Camille Garcia, a fellow student, credits Fabre herself. “I always admired her unwavering creative drive,” she says. “She would get an idea and, without anyone pushing her, execute it, efficiently.”

In January 2025, Fabre moved into 25 Moutray Street. Not long after, she opened The Living Room, a group exhibition that ran from March 28 to April 6 with work by Garcia, Müsing, and Tarar as well as Nilou Ghaemi, Emerson Maxwell, Raf Wilcot, and Fabre herself and accompanied by a text by Sharpe. The front window glowed in the winter darkness, which arrived hours before the reception. A pile of boots accumulated just inside the front door, spilling down the hallway as guests removed their footwear, most after stomping in spot on the front steps in an effort to remove some snow before entering the home. “People gathered looking and talking about art in their socks is a distinctively different vibe,” says Maxwell. “I appreciate Margot not dressing up the room as a white cube gallery. She left the old coaxial cables protruding, the hanging light fixture, and all the baseboard trim in place. It felt less corny than make-believing we were in a capital-G gallery.”

Two weeks after the inaugural exhibition closed, Fabre shared documentation of her chalk drawing diptych, Through the blinds (2025), on social media. The caption read: “Thinking about hosting a little book fair this summer, do you make books/zine? Message me.” In this simple, unassuming announcement, Fabre planted the seed of an idea.

Margot Fabre, Through the blinds, 2025. Pencil and chalk on paper. Courtesy of Nilou Ghaemi.

Photo: Nilou Ghaemi.

Eunice Luk, an artist and publisher of Slow Editions, responded to Fabre’s open invitation. She and her husband, the musician-composer Masahiro Takahashi, had also hosted a house show series called Nishi Ogikubo Uchi in Tokyo and continued the practice after moving to Toronto. Luk helped Fabre retool cardboard boxes as display stands for books, a step toward progressing beyond mutual admirers on an app.

The book fair abandoned the model of each vendor standing behind their table, monitoring guests, and other norms of such events. Instead, Fabre used rudimentary supplies—including inexpensive metal L-brackets, Styrofoam, packing tape, a plexiglass magazine rack, and the aforementioned salvaged cardboard—to transform the front room into something akin to a boutique. A tubular steel, Cesca-style chair and a vase of pink lilies added touches of domestic comfort. From noon to 5 pm on June 28 and 29, Fabre handled all transactions while Bansal sold glasses of homemade carbonated prebiotic sodas on the porch. I sipped Tamarind Orange Creamsicle as I flipped through books from approximately a dozen small press publishers.

On the Friday morning following the fair, I visited Fabre in her home again. I sat at the kitchen table as she prepared pour-over coffee for us. Neatly laid clippings of Echinacea from the front yard covered a quarter of the tabletop, after Luk pointed out the flowers, Fabre harvested and is drying the leaves and petals. Despite her willingness to follow through, Fabre reflects that her early years in the city were difficult. “It takes a while when you move to a new place to find people. I’ve always felt a bit on the outside,” says Fabre. “This feels like a new chapter to be able to have community and bring it to life in this way.”

LungA School, 2024. Courtesy of Leander Albin.

Photo: Leander Albin.