Curating Belief at the Lily Dale Museum

To visit Lily Dale is to step into a world of pure belief. Located just an hour’s drive south of Buffalo, Lily Dale is one of America’s longest-running Spiritualist camps, attracting thousands of visitors seeking psychic knowledge and spiritual healing each summer. It carries on the tradition of Spiritualism, a religion based in the possibilities of mediumship and psychic connection that emerged in Western New York in the mid-1800s. Here you can visit a professional medium, attend a Spiritualist church service, or simply take in the otherworldly ambiance. It is a space where the lines between living and dead, possible and impossible, grow thin.

Perhaps no location on Lily Dale’s grounds better exemplifies this than the Lily Dale Museum. Tucked into the back corner of Library Street, it serves as an archive of the camp’s history and an art museum dedicated to preserving Spiritualist art and artifacts. Despite its relatively small size—the building was originally a one-room schoolhouse—it holds a wide array of archival objects, original artworks, and records of anomalous experiences. Here conventional historical artifacts, such as those in the Susan B. Anthony women’s suffrage display, live side-by-side with more unorthodox relics, like the museum’s collection of musical instruments that can (allegedly) be played by spirits. Though the museum keeps one foot in the material world, it simultaneously opens the door to other concepts of reality often discouraged elsewhere.

Janet Carlill with the precipitated spirit painting of Azur, Maplewood Hotel. Lily Dale, NY, 2002.

© Shannon Taggart, from Séance.

The Lily Dale Museum takes a different curatorial approach from the scholarly detachment embraced by most cultural institutions. Instead, it maintains a sincere conviction that many of its artifacts contain genuine supernatural powers or, in cases like Dr. Rev. Clara E. Barnett’s “transition drawings,” are authentic records of psychical phenomena. Absent is the anthropological lens typically deployed by contemporary art and history museums, which relegates objects of beliefs to “other” cultures and creates a false dualism between a modern “us” and a non-modern “them.” Instead, curation prioritizing authentic belief over institutional skepticism brings visitors into the Spiritualist fold. The museum, in other words, asks its guests for their sincere belief, if only for a little while.

An example of this is its prized collection of precipitated spirit paintings, a genre that museum curator and historian Ron Nagy literally wrote the book on. These are paintings (allegedly) generated by spirits without the help of human hands. The images typically portray famous figures, spirit guides, or others denizens of the spirit world. This practice peaked in the late 1800s and early 1900s when famous medium duos, like the Campbell Brothers and the Bangs Sisters, made such paintings a key part of their stage shows. Many of these portraits depict the deceased loved ones of audience members, offering comfort to those grieving. Unlike other forms of Spiritualist art, which channelers may attribute to a spirit while acknowledging their own hand in the process, precipitated spirit paintings are unique in their (seemingly) miraculous origin.

Other institutions may present these pieces through a purely skeptical lens. There are, after all, many theories about the role played by stage magic and illusion in the production of these paintings. Yet, the Lily Dale Museum asks visitors to consider the possibility that such paintings actually were miraculously manifested and are the result of genuine intervention by spirits. This approach mirrors how other religious traditions treat their miraculous artifacts. Consider one of Catholicism’s most revered relics: the cloak imprinted with the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe through divine intervention. While skeptics may cast doubt on the Catholic belief in the image’s origins, there is still general respect for those who make the pilgrimage to see it. By asking for the same reverent treatment of spirit paintings, the Lily Dale Museum proposes that visitors examine their underlying assumptions about belief. This approach challenges us to examine which beliefs our culture considers worthy of respect—and why.

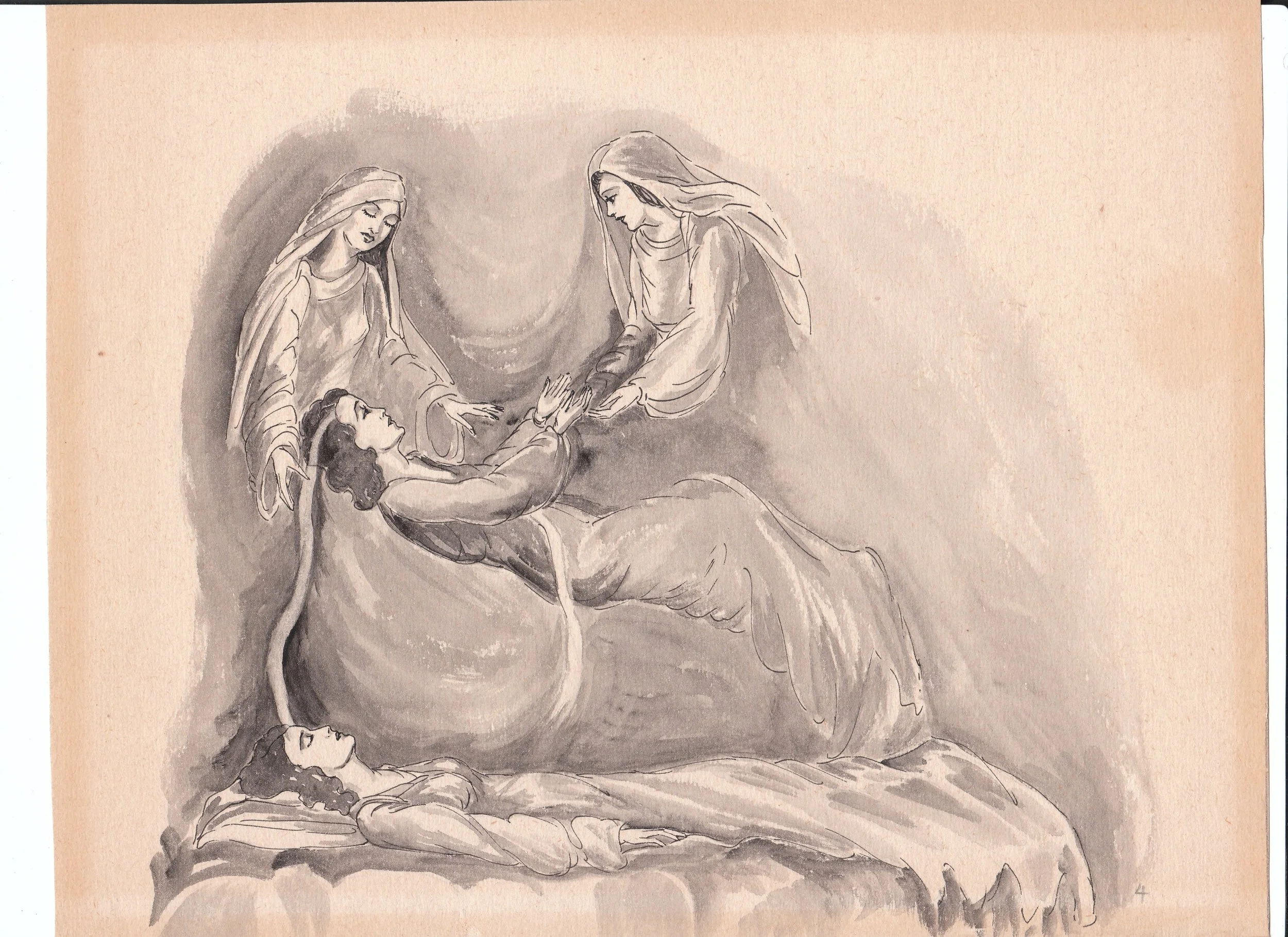

Untitled (death scene/transition drawing), date unknown. Attributed to Dr. Clara Barton. Courtesy of the Lily Dale Museum.

Although Spiritualist art is a niche genre, it is not uncommon to see contemporary institutions host shows dedicated to such work. Unlike the Lily Dale Museum’s collection, however, these exhibitions are usually bathed in institutional skepticism that prioritizes a scientific materialist view. Take the recent exhibition Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediumship organized by the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. While it featured an impressive collection of Spiritualist art and contemporary interpretations by artists like Tony Oursler and Shannon Taggart, its curatorial approach often reduced Spiritualist practices to mere stage illusions by presenting them alongside 19th century magic acts. Though Spiritualism has a unique relationship to the birth of United States stage magic, the conflation of the two comes at the expense of engaging with the authentic beliefs of Spiritualists. The curatorial foregrounding of stage magic in Conjuring the Spirit World seemed to privilege explaining supernatural claims through illusion and deception, rather than engaging with them on their own terms.

The issue with this type of curation—whether of Spiritualist art or other objects of belief—is that it too readily dismisses the possibility of multiple ways of knowing and understanding the world. The institutional faith in rationalist modes of thinking, in explaining everything through empirical evidence, tends to flatten the lived experiences of many believers. For example, the Peabody Essex Museum presented Spiritualism as a fad of a bygone era explainable through the presumed naivety of previous generations. It did not do enough to acknowledge the continuing activity of the Spiritualist community and its many successors worldwide. In Brazil, for instance, Kardecist Spiritism—an offshoot of Spiritualism—remains one of the largest religious communities in the country. Given that most of the world’s population believes, to some degree, in otherworldly phenomena, why are so many cultural institutions reluctant to embrace belief? Although some museums take a detached stance to accommodate a wider audience, they often alienate their visitors through unrelenting skepticism and an insistence on academic distance.

Ron Nagy examining a rare painting of the Fox sisters, National Spiritualist Association of Churches Headquarters, Lily Dale, NY, 2004. © Shannon Taggart, from Séance.

Admittedly, there are times when the Lily Dale Museum could use some institutional oversight. The museum’s many depictions of Indigenous people—reflecting the complicated (and sometimes troublesome) relationship between Spiritualists and Native American communities—would benefit greatly from better framing that more thoroughly explains this history. Many recent publications, like Spiritualism’s Place: Reformers, Seekers, and Seances in Lily Dale by the team behind Dig: A History Podcast and Mira Ptacin’s The In-Betweens, have reconsidered the shaky lines between allyship and appropriation in Spiritualism’s relationship to indigeneity, and the museum could better serve its visitors by leveraging such scholarship to address these complex entanglements more directly. Even the collection of artifacts related to the women’s suffrage movement—in no small part animated by early Spiritualists—can sometimes get overlooked in the laissez-faire curation. While you can read more about these histories in the museum’s small library, the casual visitor is likely to walk away without understanding these vital historical connections and complications.

The museum, however, offers something much better than wall text: a living, breathing Spiritualist historian on site ready to guide you. Ron Nagy has been at the Lily Dale Museum since the early aughts, when he serendipitously arrived in time to take over from the previous historian. He dutifully watches over the place every summer season, guiding visitors through the nooks and crannies of the collection. Ron is considered one of the world’s leading experts on Spirit art and has published several books on the topic. He has also taught classes on spoon bending and led ghost walks through Lily Dale to help guests develop their psychic abilities. You can usually find him tucked away in the corner, waiting to answer questions or give tours. He has a didactic memory for all things Spiritualism, and his knowledge extends to even the tiniest artifacts in the museum’s collection. His charisma transforms the museum from a static collection into a living archive where each artifact becomes a gateway to further stories and connections.

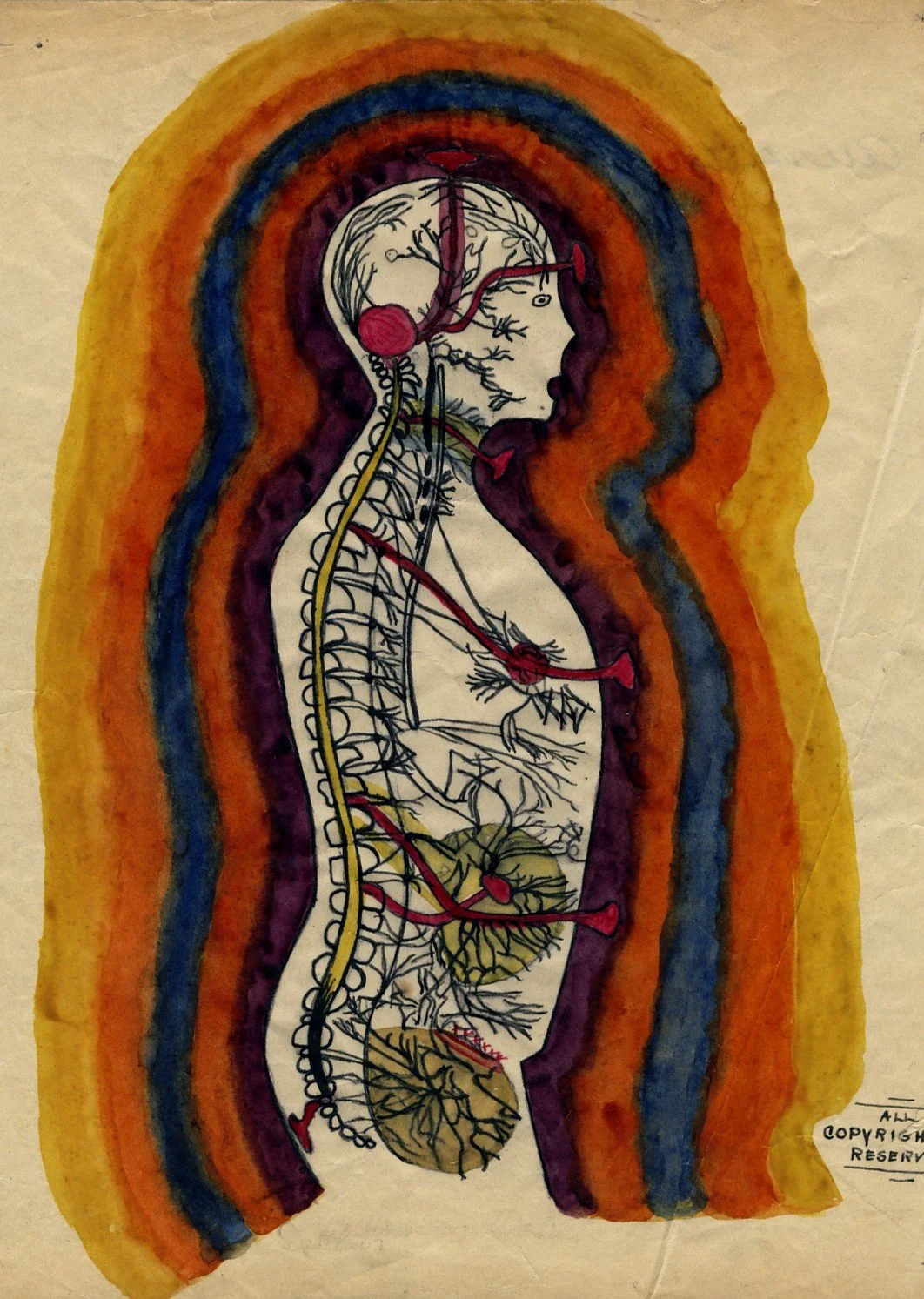

Untitled (aura drawing), date unknown. Attributed to Dr. Clara Barton. Courtesy of the Lily Dale Museum.

Ron stands as living proof that Spiritualism isn't some quaint historical footnote but a contemporary belief system that continues to attract followers who reject rigid boundaries between the physical and spiritual worlds. Discarding the distance of glass cases and academic jargon, Ron brings Spiritualism to life through his work at the museum. Here belief is not stale or inert; rather, it is as active as the community it serves. The museum remains a vibrant and important hub for practitioners and casual visitors alike, despite some of its objects dating back over a century. Even stubborn skeptics may find its break from the detached institutional curation characteristic of other cultural spaces refreshing. Especially in a culture that increasingly shies away from otherworldly matters, the Lily Dale Museum shows that curating belief requires neither blind faith nor rigid doubt—only openness to possibility.

1. Ron Nagy, Precipitated Spirit Paintings (Galde Press, 2006).

2. For example, early 20th-century psychical researcher Hereward Carrington, a figure largely sympathetic to the Spiritualist cause, published extensively on how mediums may have used illusion to achieve these paintings.

3. It’s worth noting that Taggart maintains a close relationship with the Lily Dale Museum, and eagle-eyed observers can find several of her photographs scattered among the collection.

Spirit Trumpet in the Lily Dale Museum, Lily Dale, NY, 2004. © Shannon Taggart, from Séance

by Christopher Michael

Christopher Michael is an artist and writer pursuing his PhD with the University at Buffalo’s Department of Media Study. He was born and raised in Smurf Village but left to pursue his academic and artistic interests.