Erratic Behavior:

Towards Sustainable Curatorial Strategies

Erratic Behavior, 2024, installation view, Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

Photo: Toni Hafkenschield, courtesy of KWAG.

Erratic Behaviour, recently on view at Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery and curated by Katie Lawson, features artists Catherine Telford Keogh, Diane Borsato, Kelly Jazvac, Laura Moore, Meghan Price, Robert Hengeveld, Tahir Carl Karmali, and Tsēmā Igharas. The exhibition’s title is a double entendre that alludes to the earth’s dynamic geology, which operates on a very different temporality to that of human experience, and foregrounds humans’ relationship with the earth’s strata and apparent mission to turn the world inside out. In geology, “erratics” are wandering rocks, while erratic behavior in humans is something many of us experience. For Lawson the artworks playfully “evoke the animacy of boulders and rocks [or] point to a world that is increasingly shaped by the climate crisis and faced with dwindling resources.” ¹

There is one dimension of this exhibition that I find particularly interesting and that allows for a generative discussion around curatorial approaches. It is perhaps not immediately discernible and lies not with the outcome but rather with the processes by which the exhibition emerged. Materially, and on a fundamental level, the resulting exhibition is something familiar: discrete objects and forms of matter configured, made, or designated by artists as artworks grouped together in a room. The intrigue for me, however, is in the journey, not necessarily the destination. For Erratic Behaviour, the curatorial logic complements and lends itself to the thematics at hand: geology, humans, extraction, the climate crisis, and their complex entanglements. There are a few things I hope to draw out in these reflections, namely the curatorial motivations and how these are entangled with and diverge from Erratic Behaviour’s conceptual and material themes.

Exhibition making — and making art public in its broadest sense — is an ongoing negotiation among many actors. Of course, there are the artists, since it is thanks to them that we are here doing this work. But in addition, there are curators, funders, preparators, and arts administrators, not to mention a plethora of other freelancers or contract workers. These are only the humans who are part of the process; this list does not venture into the many other arrangements of matter that necessarily contribute to and form the materials necessary to make art, the frameworks of display, and the infrastructures that facilitate art’s public reception. All of this might be obvious, but I argue that these aspects are important to emphasize.

Erratic Behavior, 2024, installation view, Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

Photo: Toni Hafkenschield, courtesy of KWAG.

In considering Erratic Behavior, I am reminded of anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli’s reflections on her time with Betty Bilawag and Gracie Binbin in the socalled Top End region of Australia’s Northern Territory. Here one learns how integral context is, how important the particularities of a place are, and how they feed into, inform, and rely on one another in myriad ways. Povinelli learns from Bilawag and Binbin about “manifestations,” which are “when something not merely appears to something or someone else but discloses itself as comment on the coordination, orientation, and obligation of local existents and makes a demand on persons to actively and properly respond.” ² Povinelli’s account of walking on the beach with Binbin and Bilawag among oysters exemplifies this coordination, orientation, and response: “But humans are hardly the only or most important existents in these practices of materializing attention. Binbin and Bilawag knew the other forms of existence were also constantly assessing them — the weight of their and my feet in the thin, slippery mud hiding the razor edges of oysters makes the point well enough. The mud, the oyster, and the weight of my body dynamically interpret each other in such a way that they produce a specific effect.” ³ I do not want to diminish or flatten these relations or merely draw like-for-like comparisons between them and distinctly human social forms like the art world. But I do want to bear in mind their importance. Our social world is always entangled with the land and other living beings at scales and in dimensions we cannot always perceive, and these entanglements are necessarily responsive and reciprocal. This thinking decenters the human being with its many assumptions, now made into one actor of many in a larger ecology. No doubt the art world is subject to innumerable pressures from individuals, institutions, and other forces that push, pull, and compromise, but this is both distinct from and entangled with the beach Povinelli walks.

Attuning to one’s surroundings is an important lesson, and it throws up lots of ethical and pragmatic concerns and questions when considering how one operates within and through the curatorial. For example, how can curators develop and work in ways that are not only critical but also sustainable, all without compromising on what the work requires, be this scale, particular standards of display, or lower-impact transportation methods over long distances? Erratic Behaviour demonstrates an engaging and generative convergence between the limitations and prospects that more sustainable curatorial practices might conjure. Lawson explains that “much of the artwork found in this exhibition resists . . . patterns of consumption and waste through a shared commitment to working with existing, found, abandoned, salvaged, and reclaimed materials. This is not only true of the artwork, but of the curatorial approach to exhibition design and methods of display, working with the materials on hand at the hosting institution.” This is one of the principal parameters set by Lawson, instigating a low-impact and somewhat circular economy of materials and methods.

1 https://kwag.ca/sites/default/files/website_files/kwag_erratic_behaviour_exguide_final_web_3.pdf

2

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 58.

3

Ibid., 60.

Erratic Behavior, 2024, installation view, Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

Photo: Toni Hafkenschield, courtesy of KWAG.

None of the artworks on display came from origins that meant traveling by plane or crossing any oceans. Plinths and shelving for the exhibition came from materials on site: the byproducts of previous exhibitions or other items that the curator had identified during their research process. The wall color remained from the previous exhibition, and all exhibition wall labels and didactic materials were printed on paper and carefully mounted, avoiding processes like vinyl lettering and the associated waste of its production, application, and disposal. Out of these parameters come challenges but also interesting and exciting possibilities and a rigorous and critical engagement with the exhibition’s themes via its very material construction.

These processes have been points of discussion and research for the Centre for Sustainable Curating (CSC) in the Department of Visual Arts at Western University in London, Ontario. CSC’s members, including Lawson, research, advocate for, and teach eco-friendly approaches to exhibition making, foregrounding low-impact materials, the sharing and reusing of resources, and other methods to reduce and counter the wasteful and polluting tendencies ubiquitous in the business of making contemporary art public. It could be understood here that the CSC is attempting to redress in some way much of the art world’s ongoing disregard of or inability to commit to sustainable practices. They are not alone in this project; the Gallery Climate Coalition springs to mind as an ally here. However, if one were to be cynical, these dispersed and unevenly distributed projects appear as a futile gesture against the seemingly unstoppable juggernaut of an international, neoliberal art world. How can an art world be both international and sustainable? What does “sustainable” in this context even mean? And, following from these questions, might it make more sense to nurture a more interconnected network of regional art worlds?

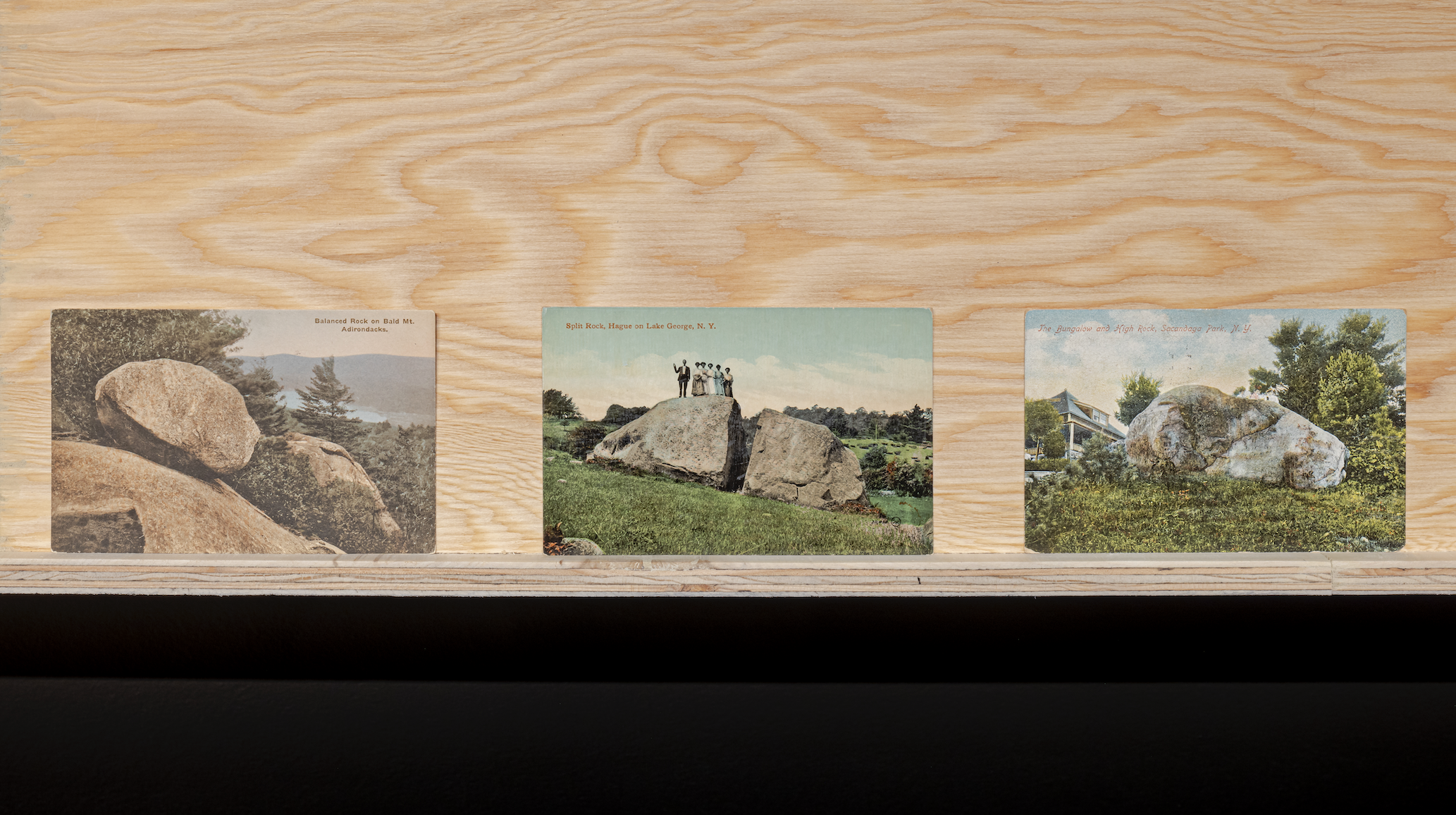

Meghan Price, Every Body is Moving, 2015-ongoing. Postcards from artist's

collection, dimensions variable.

Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenschield, courtesy of KWAG.

Much of my initial thoughts have focused on the exhibition’s curatorial framework. However, the themes that animate the curatorial ethos are rendered legible in its artworks, too. Upon entering the exhibition, one is presented with a row of postcards atop a long shelf. To the left are the introductory didactics and exhibition signage, printed on large sheets of paper echoing the same 4 × 6 ratio of the postcards. The postcards are displayed on a shelf made from offcuts of wood gathered from the gallery’s woodshop. The series of found, vintage postcards, collected and titled Every Body Is Moving (2019) by artist Meghan Price, depicts glacial erratics: large boulders sitting on their own, seemingly out of place. Melting ice sheets carried these rocks away from their original landscapes millennia ago. They then became tourist attractions and places of fascination. The postcards evoke notions around communication, circulation, connection, relationships, memory, and time. Within the exhibition there are also resonances among the postcards, what they represent, and the methods of display and interpretation that frames them: glacial erratics can only travel as far as the receding glaciers can facilitate, much like the artworks’ travel by land.

Tsēmā Igharas, high-grade copper anomalies, 2015-ongoing.

Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenschield, courtesy of KWAG.

On an adjacent wall is a selection of Tsēmā Igharas’s high-grade copper anomalies (2015–ongoing). Their forms in some respects are reminiscent of miniature copper blobs one might see in a Lynda Benglis sculpture. The sculptures consist of partially melted-down Canadian pennies, moving from one form of value exchange via currency, through to its transmutation to molten copper, and back to its solid state. Its transmutations reveal the varying ways in which copper holds value and significance, whether cultural, industrial, or economic. Here one traverses various systems of value and the detrimental means by which it is extracted; toxic waste from the mining and processing of copper are a clear case in point. The morphing of matter is also present in Kelly Jazvac’s Plastiglomerate (2013) and Laura Moore’s Future Fossils (2021). The former foregrounds the reality of new geological formations of plastic fused with natural materials to form a rock for the Anthropocene. Moore’s specimen pushes this further: one stumbles across obsolete hardware, discarded and rediscovered in the geologic record of a distant future and perhaps even a distant civilization; it is not a trilobite one encounters here.

The temporality of rocks and the slowness, or even apparent stillness, that they evoke for humans invite one to slow down. In doing so one can consider the impact, criticality, and positionality of one’s practice. Lead times may lengthen, and tasks generally understood as straightforward might become more convoluted or complicated. Certain decisions might be deferred or adapted accordingly, if current materials cannot fulfill artistic or curatorial ambitions, for example. It is a process of defamiliarization, of a newly heightened attention to one’s context.

Laura Moore, LS1655, 2021. Hydrocal gypsum cement and gouache, 7 x 4 x 5 1/2 inches.

Courtesy of the artist. Photo: LF Documentation.

A slowness that helps one to see one’s locality anew and how it is globally entangled and interconnected is abundant with possibility. The richness of contemporary artists’ research and material practices demands curatorial work that contributes to their legibility, setting up fresh critical contexts through place-specific provocations, positioning artwork and others in dialogue, and adopting carefully considered approaches to spectatorship. In the case of Lawson’s Erratic Behaviour, these commitments are emphasized through the exhibition’s regionalism This is regionalism not in a derogatory sense, freighted with insularity and provincialism, but regionalism as curatorial ethos: a serious and committed exploration to how relations within a given context may materialize and unfold, and an embeddedness in the local that provides a place-specific and contextually rich point of departure. Here there is a propensity to embrace complexity while mitigating against wasteful practices, such as excessive mileage that artworks often travel. The curatorial practicalities run through, converge with, and diverge from the exhibition, the distinctness of each artwork, and the expansive lines of inquiry they all follow. Of course, such projects and ways of working are generative, but they might also be messy and slippery, which is an exciting place for new possibilities.

by Warren Harper

Warren Harper is a curator and researcher currently based in Toronto, Canada. He recently completed his PhD at Goldsmiths, University of London, where his curatorial research project explored Essex’s role in Britain’s nuclear story. Warren has worked with and held positions at various galleries and institutions across the UK, Canada, and the US. He is also a member of the plumb, an ad hoc collective of artists, writers, and curators. You can find more of his work at www.warrenharper.info.