Microbes, Bodies, Biomes, Borders: A Pandemic Ferment

by :

Lauren Fournier

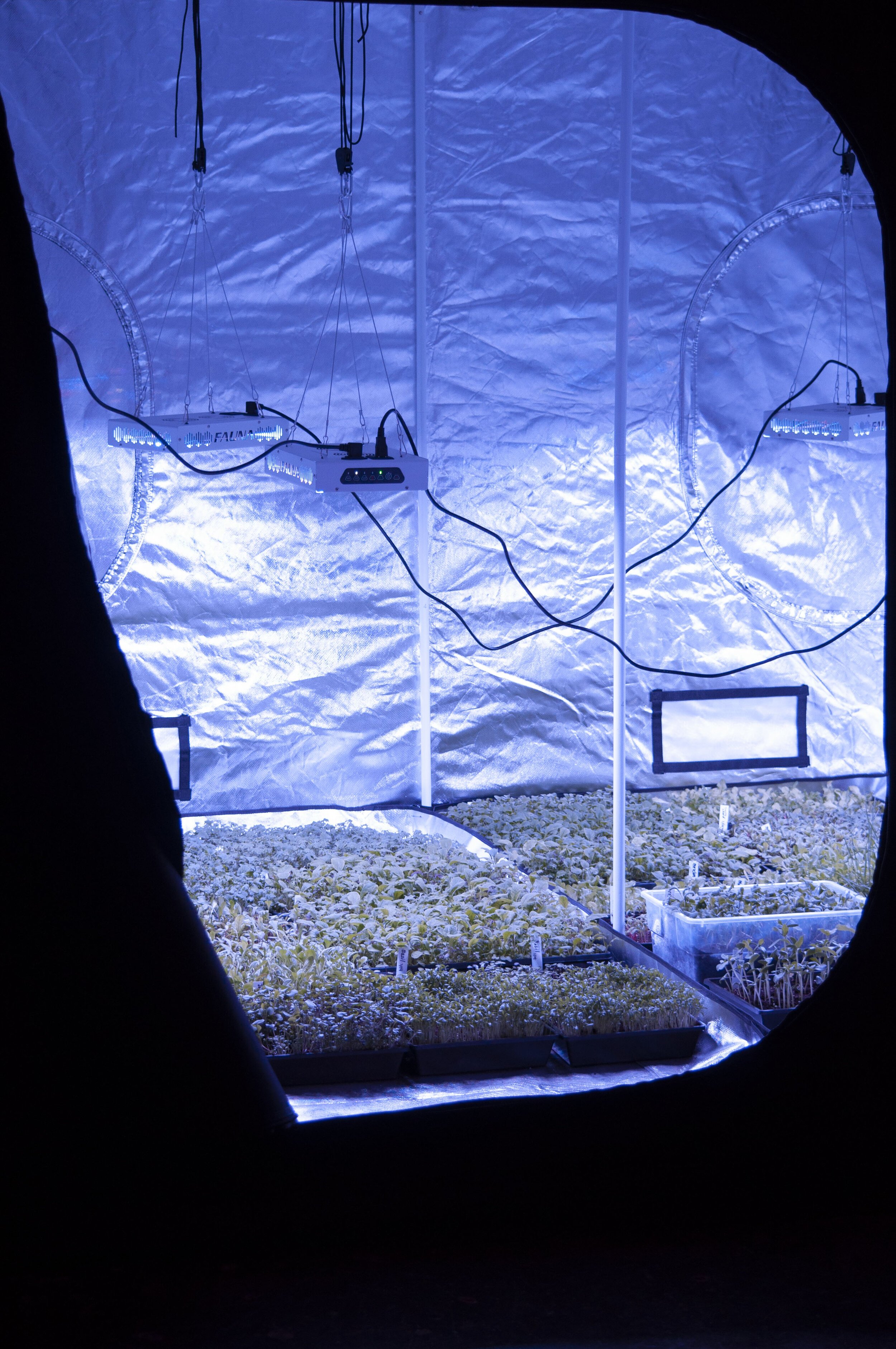

TJ Shin: Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, 2020, installation view, Recess. Photo: Mary Kang.

In the midst of a global pandemic, as I shelter in place, I have spent a lot of my time reflecting on the (im)possibilities of fermentation and microbial life. This is a time when the prevailing health message is to double down on the use of anti-bacterial wipes and alcohol-based hand sanitizers; to pour anti-microbial liquids onto our bodies, onto the food we purchase on our hopefully rare trips to the grocery store, and onto any other surface we touch; to treat spaces of entry and transition, these spaces of settling in and preparing the food to sustain us, as sites of potential danger, of trespass. A banner ad reading “Kills 99.9% of bacteria!” floats above a recipe for sourdough bread on The New York Times website, and the irony is not lost on me. It is a period of stark tensions around the microbiome and around borders — both of the body and of the nation.

In February 2020, I flew from Toronto to New York to take part in TJ Shin's residency-exhibition Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings at Recess in Brooklyn. Shin invited me based on my work with Fermenting Feminism, a site-responsive curatorial experiment I’ve been guiding since 2016. For Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, they created a greenhouse structure within the gallery space. Shin used practices of JADAM (a group of organic farmers based in Korea) to ferment lactic acid from scratch and then inject that lactic acid into the soil — an artistic/conceptual, but also quite literal, physical response to a finding that immigrants lose their native gastrointestinal microbes within 6 to 9 months of arriving in the United States. I want to bring some ferments to New York with me but am nervous about that movement across borders: live cultures are considered “biohazardous materials” and are regulated accordingly. I opt for the less risky option, keeping my living ferments at home, and bring just my microbe-laden body instead.

It was an almost utopian experience, a bunch of us crammed into an artist-run centre, sweatily sharing fermented foods and beverages and talking speculatively and excitedly about the radical possibilities of microbes crossing borders. All this in the context of Shin’s exhibition: us bathed in the magenta light that supports the growth of green plants, the probiotic-infused greenery sprouting up in the greenhouse at the back of the space, almost ready for the concluding community meal that Shin would hold there in the coming weeks. I gave a talk on the relationship between fermentation and harm reduction, standing up to weave through the crowded bodies and serve the group their own bottles of kombucha courtesy of Carlington Booch, an Ottawa-based microbrewery run by self-identified drug addicts in recovery. The owner of the social enterprise, Jon Ruby, a recovered addict and now pastor, told me this was the first time their booch traveled across international borders. Cool! After the talk, I connected with artists and designers — many from South Korea — like Seona Joung, an MFA student studying design at the School of Visual Arts. She tells me about her thesis project on the ways migration and multi-locality manifest in immigrants’ identities and their sense of belonging. She tells me that fermentation and food cultures are providing another avenue for her work as a designer, and that she is planning to lead a kimchi fermentation workshop as an opportunity to invite immigrants to share how their experiences of immigration have transformed their sense of themselves in the world. Microbes and identity, bodies and borders — we were steeped in a real sense of joy in the space, ideas bubbling up and over, us at the back of the gallery breaking sourdough bread together and spreading cultured butter on its craggy surfaces. As we chew, Shin pours small amounts of the lactic acid brew in glass beakers for us to taste. Its smell is potent, like a strong cheese.

TJ Shin: Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, 2020, installation view, Recess. Photo: Mary Kang.

Within a month of my return to Toronto, the United States-Canada border would be closed swiftly and firmly, beginning the longest closure in history of the world's longest undefended international border. Now, instead of microbial life moving across borders as part of a quite idealized, intersectional vision to free the microbiome, borders were more closed than ever. Anti-bacterialism emerged with new force, in contrast to our conversations that sought a resistance of the anti-bacterialist imperative in the name of an anti-colonial, anti-racist, anti-capitalist practice such as that realized in Shin's exhibition and accompanying programs. Each country again became its own self-contained nation-state, each like a vessel tightly shut, preventing airflow. The people within these sequestered zones started new rituals that involved expunging any trace of bacterial life around them through hand sanitizers and disinfectant wipes. It was jarring to experience such a marked shift within a few short weeks — to go from collectively imagining ways of fostering microbe-led spaces in a context of sweaty bodies in close proximity in an intimate, windowless gallery, to just as collectively but now quite un-intimately working to expunge all of the bad bacteria as a way of fending off the global pandemic for those most at risk. Almost immediately, the collective thinking around microbes, porosity, and borders had changed, now wrapped up in the politics of virality, transmission, microbial life and death. From within the confines of these enclosed nation-states protests bubble up and riots burst forth against pernicious structural forces like racism,and people are ready to fight for real social and political change, some for reform, others for revolution.

TJ Shin: M for Membrane, 2020, installation view, Wave Hill.

Central to Shin’s work as an artist is bodily porosity and microbial ecology. In the spring of 2021, Shin will be moving to Buffalo to start a residency at the University at Buffalo’s Coalesce BioArt Lab — postponed from 2020 due to on-site protocols around COVID-19. For this residency, Shin will collect bacteria from their mouth and fuse them into the genome of a mugwort plant through a gene-transference process made possible by agrobacterium. As a quintessentially “witchy” plant known for effects like lucid dreaming, mugwort is quite easily foraged in urban environments, unassuming in its presence, and grows like a weed. After the plants mature with their own DNA, Shin will dry the plants. Once dried, the artist will then burn the mugwort–oral microbe plants in collaboration with a Korean shaman as part of a body-liberation ritual.

At a time of anti-bacterial and anti-septic attitudes, Shin’s work explores the possibilities of queer kinship and intimacies with our microbial world. Following the exhibition at Recess, Shin was in residency at Wave Hill in the Bronx; there, they produced an exhibition that involved the cultivation and fermentation of soil microbes and leaf litter. In practices like Shin’s, we see that microbes are some of our best teachers: we can learn from them when we are consciously working with them. While making artworks around the greater New York region, Shin was active in community-based initiatives like composting activism. In this way, their work reminds me of the pandemic-time actions of others in the area, like the Jewish-American baker Caroline Schiff, who works tirelessly in kitchens around Brooklyn and encourages the preservation of food waste and fighting food insecurity through simple practices like making and eating the “sourdough pancake” — literally, the excess sourdough starter poured onto a pan.

My starter is like my baby. I’ve kept it alive for four years now. Sure, it’s not a human baby, and it’s very durable — it can stay alive for quite some time in the fridge. I take Schiff’s suggestion and make myself a pancake each time I prepare a loaf of sourdough bread. When I am pulling the dough, not kneading but pulling, I press my face up to the dough and inhale deeply, taking in its salty-oceanic scent like it’s the origin of the whole wide world.

Later in the summer, as we continue to shelter in place, the Toronto-based artist Andrea Creamer tells me over the phone about collaborative Zoom-based sourdough performances led by an artist named Lexie Owen. Owen, from Vancouver and now based in Oslo, invites collaborators to commit to a full day for the workshop/event, moving through the day together with the various foldings of the bread until the end of the day, when each of the resulting bread boules are baked. Owen’s interactive performances are digital and durational, using the medium of Zoom for an all-day gathering that allows the participating bodies to move through their lives in their own kitchen spaces. Watching one another bake and work the dough at leisure, coming in and out of conversation marks a different kind of experience from sitting, through back pain, at yet another work-related Zoom meeting. Facilitated from a distance, Owen encourages the participants to feel at home in their bodies and spaces while in dialogue with this small group of others, all separated by long geographical distances, across transnational borders.

TJ Shin: Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, 2020, installation view, Recess. Photo: Mary Kang.

Earlier that spring, I started following a number of compelling sourdough bakers who seemed to acknowledge that sourdough brought something necessary in these days of sheltering in place. Some of the bakers do live talks in conversation with others — casual live-streams in their domestic spaces — and others post recipes. Schiff was soon a favourite, alongside Bryan Ford, a baker based in New Orleans who had just launched his book New World Sourdough. I tune in to a talk between Ford and a representative from the Ooni Pizza Oven company: they were talking about Ford’s new book and his recipe for Honduran-inspired sourdough rolls. That week, the context of Black Lives Matter and the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis was the backdrop for everything, and Ford, a Black American, noted in the conversation how he would be donating 5% of the lifetime proceeds of his book to BLM-related organizations. In between speaking about the powers of sourdough bread baking and the cultural mixing that happens in his recipes, Ford stated how it’s a shame that “we’re still fighting this shit — racism,” and that hopefully, over the course of his life we will not have to fight in the same way, that we’ll get to the realization that “we are all the same race — the human race.” Over talk of bread dough and fancy ovens, of recipes and the transformative action of wild yeast with wheat, Ford allows us to imagine a future of full, whole lives for more people — one in which the rights to life and good livelihoods are affirmed, regardless of race.

Over in Rochester, NY the Afghan-American artist Leila Christine Nadir continues her work with fermentation and art as part of her larger practice as an artist, writer, activist, and educator. The founding director of the University of Rochester Environmental Humanities Program, Nadir often works in collaboration with her partner, the new media artist Cary Peppermint, as part of the collective formerly known as EcoArtTech. In their ongoing School of Live Cultures, begun in 2016, Nadir and Peppermint work with at-risk youth in Rochester, hiring them for paid positions as part of a collaboration with Seedfolk City Farm, the Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence, and the University of Rochester. The artists facilitated conversations and taught local youth about sustainability and food justice, growing what they call "ruderal communities.” “Ruderal," in a scientific, botanical sense, describes those plants that grow in waste ground, among refuse or discard, or in places where the natural vegetation cover has otherwise been disturbed by humans. These “ruderal communities,” then, suggest a way of intervening in and reimagining the urban ecologies of the Rust Belt United States.

TJ Shin: Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, 2020, installation view, Recess. Photo: Mary Kang.

Nadir and Peppermint have long espoused the benefits of eating fermented foods to resist the forgetting of so many cultural food traditions that foreground spontaneous fermentation and microbial life, what they call "industrial amnesia." Their resistance also takes the form of teaching the basics of food preparation and fermentation to local communities in accessible and sensorially dynamic ways. This spring, in the early days of the pandemic, the exhibition Digestive Systems at Pace University in New York included the artists’ Microbial Selfies (2017) photo series and Nadir’s video Probiotics of the Kitchen (2015), a re-staging of Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) showing the process, from start to finish, of making sauerkraut. The video was shown next to a row of fermenting beverages and foods in bottles and jars, each labeled for ease of understanding. In Microbial Selfies, the artists blur the boundaries between fermented foods/beverages and humans, using new media and hacking alongside cooking and fermenting to create a work in which fermenting materials “take their selfie” through the pH shift of biochemical reactions. Now, Nadir has turned her attention to writing her autobiography, focusing on the borders of intergenerational trauma and what we inherit in our bodies. Fermentation continually crops up in her art, and I wonder with a keen curiosity in what forms her future work will address food, microbes, bodily memory, and memoir.

The pandemic has forced many of us to reconsider priorities both for ourselves and in relation to the others around us. For me, this reconsideration of how I shape my existence in the world is also a reflection on my relationship with food and fermentation, and how these more sustenance-based practices and passions tie into my work as a writer and an artist-curator. The borders are still closed — I was supposed to be in France this fall, spending the month of October in Paris and the month of November in Montpellier as part of a transatlantic curatorial residency awarded through the Fonderie Darling in Montreal a short month before the pandemic took hold here in Canada and the United States. The project I proposed was an exploration of fermentation and art practices in the geographical context of France that would consider, through a hybrid curatorial/writerly and food-based practice, the ties between France and French Canada from the perspective of my own strained ancestral ties to French and Basque traditions. The hands-on research for this residency, working with a great many others in small, enclosed spaces — galleries, museums, restaurants, bars, kitchens — would serve to fill the empty glass that was my family memory, providing me with insights to bring back to Montreal. For now, I shelter in place in Saskatchewan, spending this time reading cookbooks, only seeing others through the mediation of the screen. It is a different kind of fall. I wonder what next year will bring.

TJ Shin: Microbial Speculation of Our Gut Feelings, 2020, installation view, Recess. Photo: Mary Kang.