Hidden Territories

Visionary artist G. Peter Jemison transformed a historic Seneca site into an important Indigenous arts hub. Now he’s focusing his studio practice on our relationship with the land.

G. Peter Jemison, Dried Geometry, 2005. Oil and acrylic on stretched canvas, 48 x 36 x 1 7/8 inches. Collection Buffalo AKG Art Museum. Courtesy of the Seneca Gaming Corporation and the Seneca Nation, 2022. © G. Peter Jemison.

Orenda, the Haudenosaunee faith in a spiritual force present throughout all creation, is a glowing thread woven through G. Peter Jemison’s sprawling career. This power manifests in his art, from his poetic paintings about the land, flora, and fauna with which his family has been in covenant for centuries to his mixed media works that grapple with the region’s various conflicts and devastation over time.

Jemison’s art is about love of a place. For six decades, he has incorporated locally relevant political and social commentary, cultural memory, and his relationship to the natural world in his paintings, video storytelling, and mixed media works on paper.

His landscape paintings have always buzzed with a reverence for nature — even in the frozen, gray stretches of winter — and he says one of his enduring inspirations has been the simple geometries created by shadows falling on the snow.

“I've really done a lot of drawings of these shadows; some are cast by dried plants growing in the woods or alongside the road,” he says.

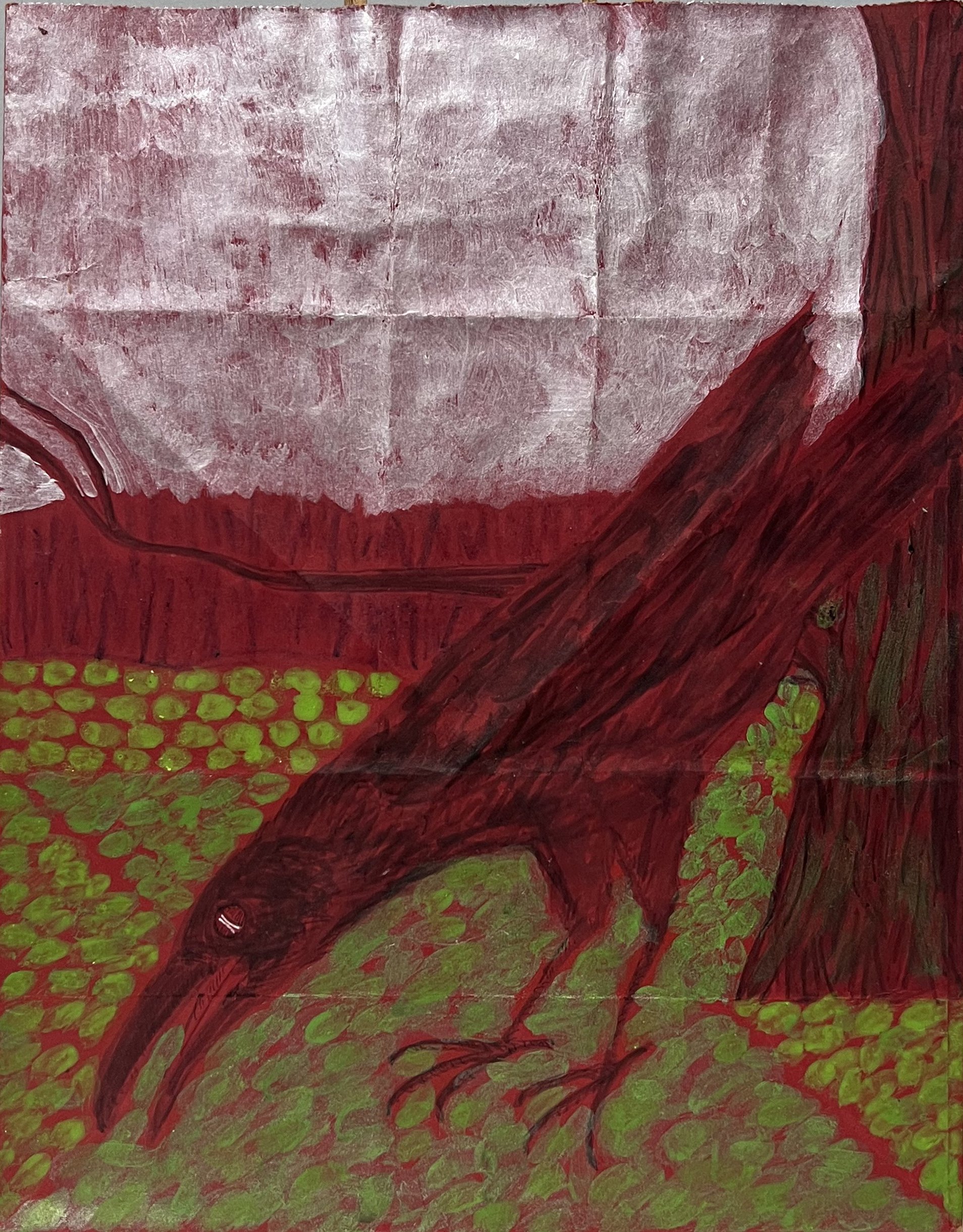

Beyond mere shapes and contrast, he records the invisible, energetic potential around the stalks of plants, their husk structures seemingly ready to quicken and provide again with the sun’s return. Some works are populated with tough scavenger birds who stick it out in stark playgrounds through the harsher seasons. Veneration of the land and defiant survival fill Jemison’s perspective, and that’s political, too.

G. Peter Jemison, Threading the Needle in Black, White, and Red, 1997. Mixed media on paper bag, 14 x 6 x 8 3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and K Art. © G. Peter Jemison.

At seventy-eight, Jemison (Seneca, Heron clan) is in his studio almost every day, working on new visions of the region and its history for two exhibitions in the fall. He says he hasn’t been able to dedicate this kind of time to his art for decades.

Jemison was the first manager of the Ganondagan State Historic Site in Victor, New York, a position he held for thirty-six years before retiring in 2022. Under his stewardship, the team at Ganondagan transformed the rolling hilltop where a Seneca village razed in the seventeenth century once thrived into one of the most important centers for Indigenous arts and culture in the United States. The site, which today includes the Seneca Art & Culture Center (SACC) and a bark longhouse complete with replica seventeenth-century furnishings, serves as both a tangible museum of suppressed history and a forum to foster contemporary Indigenous culture, philosophy, and community.

Even in retirement, Jemison helps organize major undertakings at the SACC, including this past summer’s Indigenous Music & Arts Festival, an annual showcase of traditional and contemporary tunes, dances, story-telling, and craftsmanship of global Indigenous cultures. He also still facilitates the White Corn Project, which brings Indigenous and regional communities together to husk and process the heirloom plant into foods that are sold commercially.

Jemison is instrumental in the annual commemoration of the Canandaigua Treaty (1794), one of the oldest alliances formed between Indigenous peoples and the United States, then an emerging nation.

Jemison calls the November celebration “an expression of our understanding of sovereignty, our relationship with the United States, and the rights articulated in the treaty.”

G. Peter Jemison, Plastic, 2022. Colored pencil, ink, and collage on plastic bag, brown paper bag, 22 1/2 x 7 x 14 inches. Courtesy of the artist and K Art. © G. Peter Jemison.

The work of reminding the state and its settlers’ descendants that First People still exist here, and have some useful answers to modern problems, is ongoing.

But Jemison says that, for the most part, he’s stepped back from the administrative duties that have for so long occupied the lion’s share of his time.

“It’s refreshing to be able to make the art first, and then the other requests that I receive are secondary,” he said.

In January 2023, he received the Johnson Fellowship for Artists Transforming Communities, a $70,000 award given annually by the nonprofit Americans for the Arts in support of artists whose work has some positive bearing on civic life, especially in rural places and tribal communities.

In its statement honoring Jemison, Americans for the Arts noted his work creating space for other contemporary Indigenous artists: “His visionary efforts over decades have helped lay the groundwork to bring Indigenous perspectives into curation and cultural equity concerns.”

Jemison was also honored last year by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, which added five of his works to its collection. His 2005 painting Dried Geometry now hangs on the third floor of the new Gundlach Building. It’s one of Jemison’s shadow works, inspired by winter in Western New York and, more specifically, a trio of sacred providers, enchanting even in their slumber.

“At Ganondagan, we have a garden where we grow the Three Sisters — the traditional Seneca crops of corn, beans, and squash,” Jemison says. “And occasionally we also do birdhouse gourds, which need a trellis to hang from, because they grow from a vine.” The painting is a winter scene with the dried plants and the trellis — structures natural and artificial now stripped of their heavy bounty, forming an overlapping, architectural framework made more complex by its shadows on the snow and the striated winter sky.

The Seneca Niagara Resort & Casino originally purchased the work, but Jemison says he wanted it to be accessible to more viewers, and he had also dreamed of his work hanging up at the museum. “You have to understand, I went to school across the street from the Albright-Knox at Buffalo State, and I spent a lot of time in that museum when I was beginning as an artist,” he says.

Jemison recalls his college years and his twenties as full of freedom and initiative and some tumult.

In the 1960s, the museum’s admission was five bucks, and Jemison spent days dissecting brushstrokes in the galleries and poring over the museum’s collection of exhibition catalogues and other art tomes, learning as much about breaking out of aesthetic boxes and successful curation from these resources as he did from classroom instructors across the street.

“You could just look to your heart’s content,” he says, “and the only provision [in the library] was ‘don’t put anything back on the shelf, we don’t wanna get anything mixed up.’”

G. Peter Jemison, Jeannette (detail), 2002. Mixed media on paper bag. Courtesy of the artist and K Art. © G. Peter Jemison.

He was drawn to Robert Rauschenberg’s layered materials and meanings, and he says that he learned to paint with oils by studying Chaïm Soutine’s work. He was specifically drawn to the artist’s large scale 1925 work, Carcass of Beef — a luminous portrait of muscle and connective tissue and bone that fills the canvas and senses — in the AKG’s collection. “He was one of the first artists I emulated,” Jemison says. “I literally created a painting of a dead chicken. A large one.”

Jemison graduated from Buffalo State University in 1967 and headed to Hell’s Kitchen, where he recalls watching from his apartment window as buses lined up at the Port Authority Bus Terminal, poised for departure to New Jersey. He honed his art when he wasn’t working as a delivery driver — running art supplies from a store in Greenwich Village to fashion houses, art schools, and artists all over New York — and as a display designer for a shop on 57th Street.

“I saw an advertisement and just talked my way into the job,” Jemison says. “I literally had no experience as a display artist at all.”

Jemison was part of an emerging artists invitational that year at Tibor De Nagy, then located at Fifth Avenue and 57th Street. This was another result of talking his way into an opportunity. “I had a chance meeting with [Tibor de Nagy] at the Whitney Museum, and I told him I had some work he might be interested in,” Jemison says. “He said he’d come to my studio to take a look, and unbelievably, he showed up.”

After the opening of the invitational, Jemison went back to the Whitney because the Biennial was on. He noted that a few fellow artists from De Nagy’s invitational were also in the Biennial. “And, of course, that led my friends to conclude that I had really made it,” he said. “It was kind of like a rocket ride up, because I had only been in New York about nine months, and then all of a sudden, I had kind of accomplished what I had set out to accomplish.”

But careers are full of starts and stops. Jemison came back to Buffalo the following year in a deep depression, a tender twenty-three-year-old seeking stability.

“I was young and broke, and I was really struggling,” he says. “And you know, recreation was partying, and that can have bad results.”

It was a good thing to be back on familiar ground, which played a role in restoring him. “And eventually I had a new challenge that took my mind off of this depression I was in,” Jemison says. “One day I woke up and everything looked good again. I was on my way.”

Jemison’s roots in the Buffalo area run deep. He bought his parents’ home in Irving, where he grew up across Cattaraugus Creek from the Seneca Nation’s Cattaraugus Territory.

While his father was raised on the Cattaraugus reservation, Jemison’s mom is from Allegany, the other Seneca territory located in the Southern Tier. His ancestors are Seneca on both sides, and he gets his surname from Mary Jemison, a Scots-Irish captive who chose to stay with his people eight generations back.

Jemison spent his youth rambling between Irving and his grandparents’ house on the reservation across the bridge.

“We had the woods. We hunted, and we roamed around the creek and built various rafts to get on the creek and across the creek and do whatever kids do,” Jemison said, adding that these excursions caused endless grief for his mother, who knew the waterway was polluted.

G. Peter Jemison (Seneca, Heron Clan), Artist, Curator, Historian, Educator. Photo: Tina MacIntyre-Yee, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle.

After returning to Western New York in 1968, Jemison began to dig deeper into what it meant to be Seneca and met more relatives on his mother’s side. In 1975, his nation hired him to be an education program director. He learned the language, delved into traditional culture, and began to keep up with contemporary politics that directly impacted the Seneca Nation.

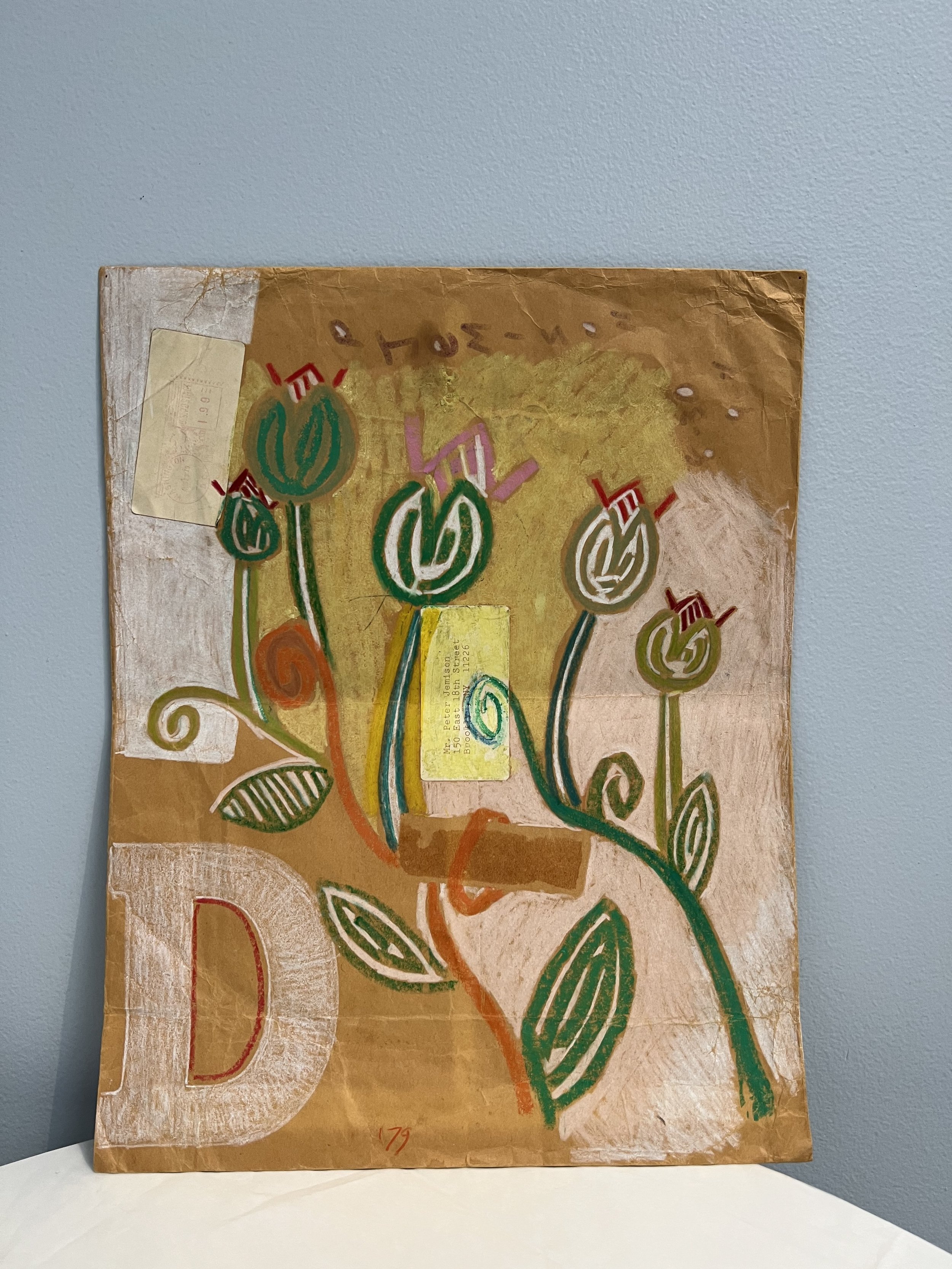

Jemison moved back to New York in 1978, and he became the founding director of the gallery at the American Indian Community House in Midtown. Living in Brooklyn, his commute to work inspired a shift in the materials he chose for his artmaking.

“I had to take a pretty good, long train ride,” he says. “People spoke everything but English. But one of the things we had in common was that people carried bags. Whether they had been shopping or whether they were carrying their lunch bag or their briefcase, people were carrying something with their stuff in it. I kind of fastened onto the paper bag as something that was really com- mon and universal.” His drawings and collages on paper shopping bags made use of a pre–social media medium for viral messaging. Jemison transformed the branded shopping bags with illustrations of history, political and social commentary, animals, and familiar terrain.

Jemison’s works on paper and paintings have found permanent homes in significant museum collections including the Heard Museum in Phoenix, the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, the Denver Art Museum, the British Museum in London, and the Museum der Weltkulturen in Frankfurt, Germany. When Jemison moved to Victor and became the site manager at Ganondagan in 1985, he continued to advocate for contemporary Indigenous artists by curating exhibitions that centered native art, and he embarked on a thirty-year push to build the Seneca Art & Culture Center, which opened in 2015.

Jemison’s recent art is monumental. In 2021, a replica of his massive, cosmogony-referencing painting Water is Life was installed on the side of Rochester’s convention center, at the intersection of the Genesee River and Main Street.

He’s currently working on several large oil paintings. One is part of a series about the formation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and focuses on historical individuals “who were instrumental in spreading a message of peace and unity to our people at a time when we were preoccupied with war and killing each other,” he says.

Another is a massive four-by-eight-foot landscape with a giant fence running across it. The whole world is fractured into wire-framed divisions, tidy little diamond portals carving up imaginary territories. From that one perspective, at least.

“I still maintain that idea of art being able to help people to really see,” Jemison says. “Not just what is hanging in front of them, but opening up a channel so that they see things out in the world they hadn't focused on previously in their surroundings, whether it's natural or manmade.”

G. Peter Jemison, D Train, 1979. Mixed media on paper envelope ,14 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and K Art. © G. Peter Jemison.