Slipping into Darkness

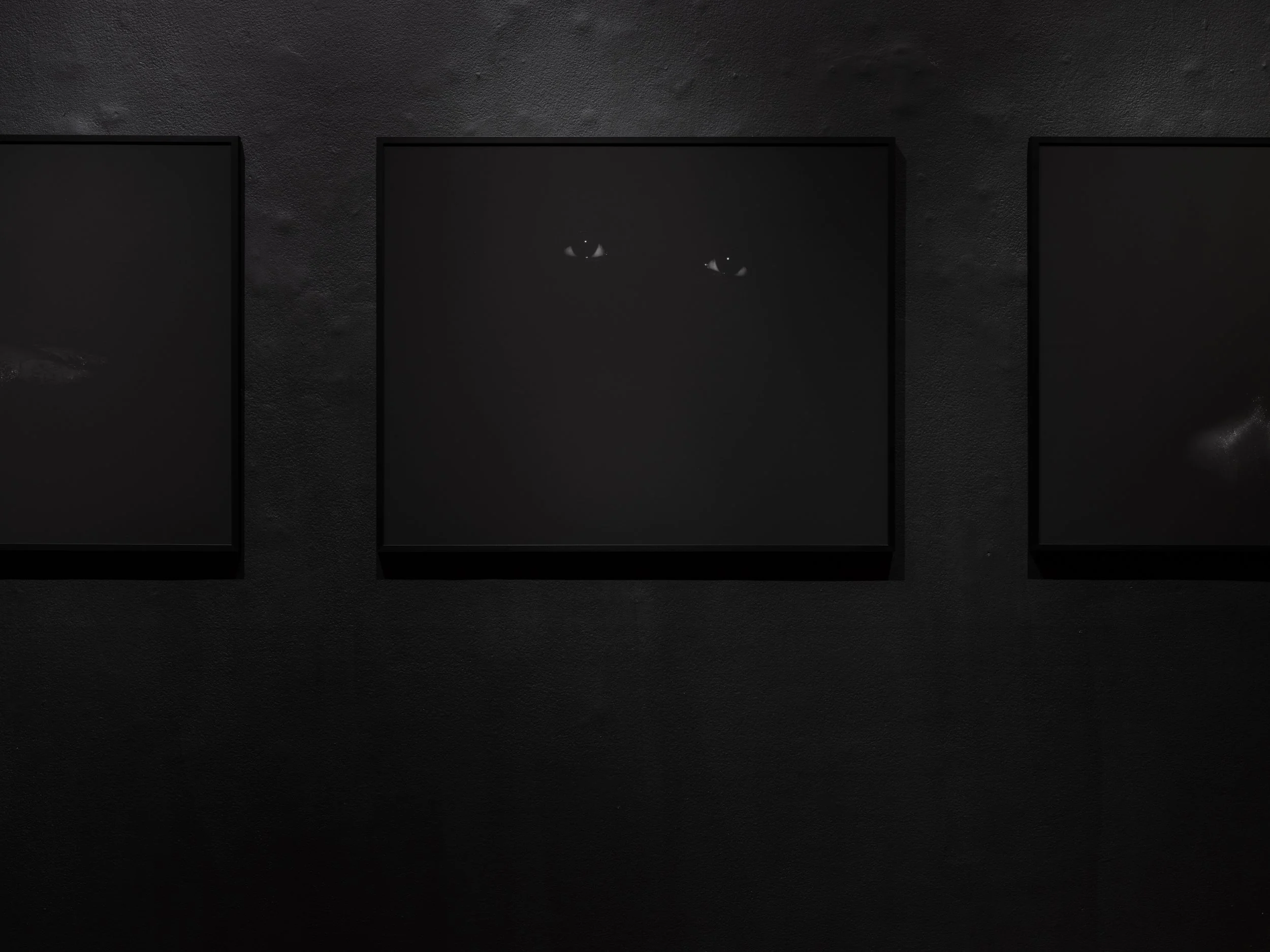

Granville Carroll: Black Serenity, 2025, installation view, CEPA Gallery.

Courtesy of the artist.

The photographic tradition is grounded in recording light to contain and preserve a moment in a carefully composed single frame. But it is an overpowering darkness that defines each photograph in Granville Carroll's Black Serenity series, on view this past fall at CEPA Gallery. Conceived in near total darkness, these untitled self-portraits act as cosmic portals transcending any singular point in time. Blackout curtains and low light extend this darkness into the physical gallery, immersing viewers in the void Carroll has constructed.

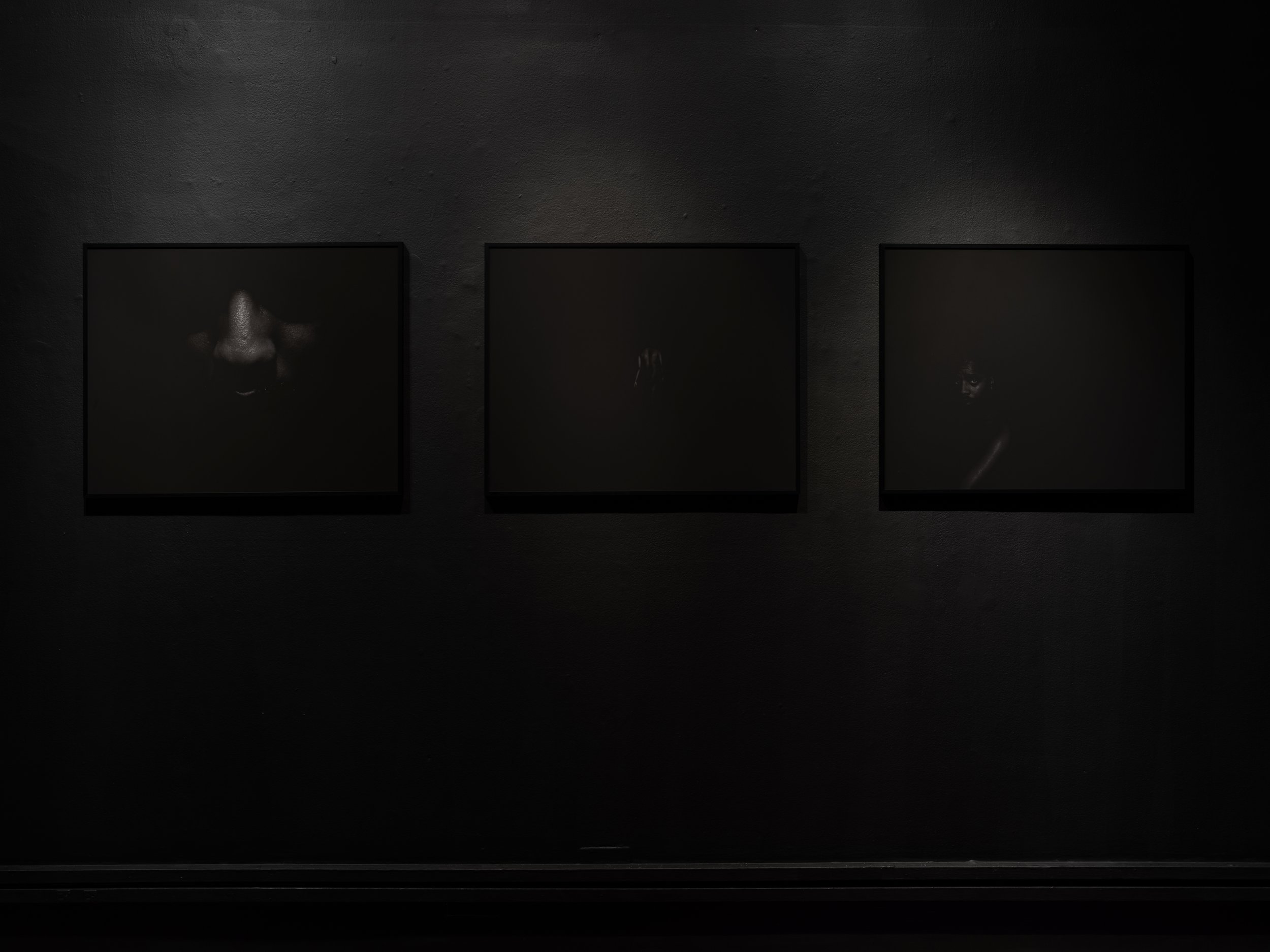

As one becomes oriented within the space, the compositions of Carroll’s photographs reveal themselves slowly and in succession. The artist has intimately posed for and configured each photograph to expose fragments of his face and body on his terms. In Untitled (2019), Carroll’s ear and shoulder are the only visible parts of his profile. His arm wraps around the back of his neck in a comforting self-embrace. Another portrait centers his face, photographed from above and half catching the light as the other half slips into darkness. His hand rests delicately on his chest as he looks into the camera with anguish, longing, and pain. This intensity of feeling is also palpable in Untitled (2018). Carroll’s hands are the focal point of the image; they cover his face completely, concealing his raw emotion. But other works remind us that with pain comes release. In one stirring portrait, the barely perceptible artist floats in water. His eyes are closed as he is baptized with a renewed sense of relief, peace, and serenity.

Throughout the exhibition, blackness operates as both a constructed identity and a place of restorative connection where Carroll no longer needs to maintain hyperawareness of the societal perceptions imposed on his body. Blackness is “transformed from a mere descriptor into a metaphysical place—a realm that is soft in its embrace, expansive in its possibilities, and profoundly sacred in its essence.”1 The artist immerses himself in a space of richly dense grays and blacks with no clear beginning or end. The unseen can trigger a primal need to run or hide as much as it can liberate and protect. Paradoxically in this space of the unseen, the depth of his vulnerability is laid bare. He is safe to be angry, sad, fearful, relieved, hopeful, and selfish without judgment. Liberated, he reconnects with himself, both physically and spiritually, in complete solitude.

1. C. Rose Smith, “A Multiplicitous Existence: On Granville Carroll's Black Serenity,” in Black Serenity: Granville Carroll (CEPA Gallery, 2025), 1.

Granville Carroll, Untitled, 2018, installation view, Black Serenity, 2025, CEPA Gallery.

Courtesy of the artist.

Black Serenity thoughtfully and carefully considers the question of where Black people—and in this instance, a Black man—can fully exist in the nuances of their emotions. The fullness of Carroll’s work reminds us of the restorative potential of the dark. It is where we rest, where we release, and where we pray. Solitude, he reminds us, “gives us the ability to transform,” allowing the body to become an “active conduit to forces beyond our physical senses.”2 Transcendence through self-portraiture connects Black Serenity to a legacy of identity formation across time and space. He notes that Afrofuturism in particular “provides a sense of freedom beyond colonial perspectives,” allowing him to look both backward and forward simultaneously.3

Black artists have long explored the potential of liminal spaces as grounds for identity formation, (re)connection to an ancestral past, and the imagination of radical futures. Born out of darkness and the theft of collective identity, Blackness is constructed and reconstructed from the fragmentations of infinite possibility. Artists like Sun Ra, a foundational figure in Afrofuturism, reimagine Blackness as out of this world, as everything and nothing. Other cultural producers, ranging from Octavia Butler to Janelle Monáe, John Jennings, and so many others, have expanded Afrofuturist sensibilities and Black world-building across disciplines and time periods. Black photographers have also made visible some of the unseen and divine connections within the dark. Roy DeCarava employed strategies such as close crops, slow shutter speeds, and smooth tonal ranges to elevate scenes from his Harlem surroundings from one-dimensional representations of “the Black experience" to more formally abstract visions of multidimensional Blackness. Fellow Kamoinge Workshop member Ming Smith similarly leveraged low light, slow shutter speed, and blur, documenting cultural icons like Sun Ra and Grace Jones in the subdued jazz clubs and gathering spaces where ancestral spirit is called upon through Black musicality.

2. Quoted in Robert Hirsch, “Granville Carroll on Black Serenity: Showcasing the Invisible,” in Black Serenity: Granville Carroll (CEPA Gallery, 2025), 3-4.

3. Ibid., 5.

Granville Carroll: Black Serenity, 2025, installation view, CEPA Gallery.

Courtesy of the artist.

Contemporary artists have further extended this temporality of Blackness, using static and moving images to complicate its construction and relation to hegemonic systems of power, surveillance, and mainstream visual culture. Arthur Jafa’s visually striking cinematic video works combine pop culture, music, fine art, and historical footage to suspend viewers in the liminal complexities of Black experience. In Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), he montages clips of civil rights leaders, iconic cultural moments, and police violence against Black bodies alongside a blended soundtrack of gospel and hip-hop. The spiritual and social undertones of the work illuminate a spectrum of Black life marked by both triumph and tragedy. Zora J Murff’s photographs, assemblages, videos, and texts similarly engage the social functions of images to examine the reverberations of oppression throughout the past and present. Nick Drain’s multidisciplinary practice interrogates the complex relationships between Blackness, the politics of visibility, and the photographic image. Their 2020 essay “What Are You Looking At? On blackness, images, and (in)visibility” unpacks photography’s oppressive and violent impact on Black bodies. Theorizing the interconnections between photography’s technological developments and images of Blackness vis-a-vis the white, patriarchal, hegemonic gaze, Drain argues that the photograph has been “a tool of epistemological violence in service of colonialism, surveillance, and other systems of oppression.”4 They reference multiple historical cases of photography positioning Black people at polarities of hypervisibility and invisibility, extremes that each possess their own oppressive dangers.

The works of Jafa, Murff, and Drain highlight mainstream visual culture’s power to shape perceptions and constructions of Blackness. Carroll's exploration, by contrast, is self-reflective. Choosing to turn his contemplation inward is a radical act of (re)constructing his subjectivity on his own terms. bell hooks notes that for members of groups historically oppressed under white supremacist, patriarchal hegemony, liberation requires the formation of one’s own subjectivity beyond the confines of these systems.5 However, market trends in recent years raise the question of whether it is truly possible for artists to free themselves from these structures or if the commodification and eventual exploitation of Blackness is inevitable. The Black Lives Matter movement and the racial reckoning that emerged in the summer of 2020 prompted a surge in sales for Black artists, particularly those working in portraiture. Museums, galleries, and collectors responded to calls for increased diversity, equity, and inclusion in cultural spaces by rushing to fill gaps in their collections and artist rosters. However, the all-too-predictable backlash against DEI initiatives and growing conservatism in the wake of the United States’s 2024 presidential election burst this bubble just as quickly as it had boomed. The explosion of interest in purchasing black art disintegrated as “anti-woke sentiment . . . infected the mainstream and interest in showy egalitarianism and visible diversity” waned.6 This market instability comes amid increasingly aggressive political attacks on institutions and funding structures that uplift culturally specific histories and identities.

4. Nick Drain, “What Are You Looking At? on Blackness, images, and (in)visibility,” Bunker Review, November 27, 2020, https://bunkerprojects.org/what-are-you-looking-aton-blackness-images-and-invisibility/.

5. See bell hooks, “The Politics of Radical Black Subjectivity,” in Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics (South End Press, 1990).

6. Rachel Corbett, “How the Black Portraiture Boom Went Bust,” Vulture, May 8, 2025, https://www.vulture.com/article/art-market-black-portraiture-boom-burst.html.

Granville Carroll: Black Serenity, 2025, installation view, CEPA Gallery.

Courtesy of the artist.

As artists contend with such stark realities and a society that continues to profit from cultural identities it seeks to erase and exploit, one wonders where refuge can be found. In “What Are You Looking At?” Drain considers selective visibility as a possible counter. The artist makes use of author and professor Simone Browne’s idea of “dark sousveillance” as a response to the histories the essay explores and a fundamental throughline in their work:

The practices of dark sousveillance, specifically the “tactics used to render one’s self out of sight,” when contextualized against the history and projected futures of Blackness in relation to the image, are the foundation upon which I situate my thinking and work on Black practices of selective visibility. . . .Through my work, I look to demonstrate the violent impact of the image in its relation to Black people; honor the methods of selective visibility that Black people have already come to practice; and imagine new ways for Black people to render themselves visible and invisible at will, rotating the viewer—subject—maker relationship to place the Black subject at the top, returning agency and power in doing so.

Carroll incorporates this notion of selective visibility in Black Serenity, making his subjectivity both visible and invisible at his discretion. In one portrait, he is completely immersed in darkness, and we can only see the whites of his eyes. His gaze is direct, and the weariness he carries confronts us head-on. The blackness of his body and his environment coalesce into one, and the innermost truths of his spirit remain. Conversely, in another photograph, remnants of the back of his bare body in the distance catch faint glimmers of light. He is exposed—yet we hardly see him. Descending into the darkness, he walks firmly into an intangible veil of reclaimed protection and power.

These photographs, like the rest of the series, create a moment of stillness within polarities of fear and hope, exposure and obscurity, confrontation and resolution. The discomforts of these polarities feel like an ominous unknown in which we’ve become collectively and deeply entrenched in recent times. Fortunately, Black Serenity reminds us that in the darkness of the in-between, there is as much uncertainty as there is possibility.

Granville Carroll: Black Serenity, 2025, installation view, CEPA Gallery.

Courtesy of the artist.

by Tiffany D. Gaines

Tiffany D. Gaines is a writer, curator, and photographer. Her multidisciplinary, research-based practice explores stories often excluded from the mainstream canon to engage new, diverse perspectives and activate the past to inspire a more understanding and empathetic future. She currently works as a curator at the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, New York.